Book of Abraham Insight #12

As a central figure in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, there are many extra-biblical traditions about the life of the patriarch Abraham. These sources are important to study because they may contain distant memories of real events in Abraham’s life. It is also interesting to compare the Book of Abraham with these sources because the Book of Abraham might help us understand these extra-biblical sources better and vice versa.

Much of the Book of Abraham’s content that does not appear in the Genesis account parallels the extra-biblical material from these religious traditions.1 Just some of the unique elements in the Book of Abraham that are found in ancient and medieval Jewish, Christian, and Islamic sources include:

- Idolatry in Abraham’s day

- A famine in the land of the Chaldeans

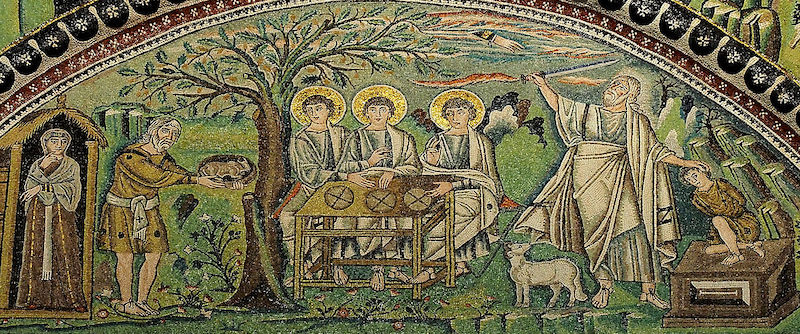

- An attempt to sacrifice Abraham

- Abraham receiving a vision of God and the cosmos

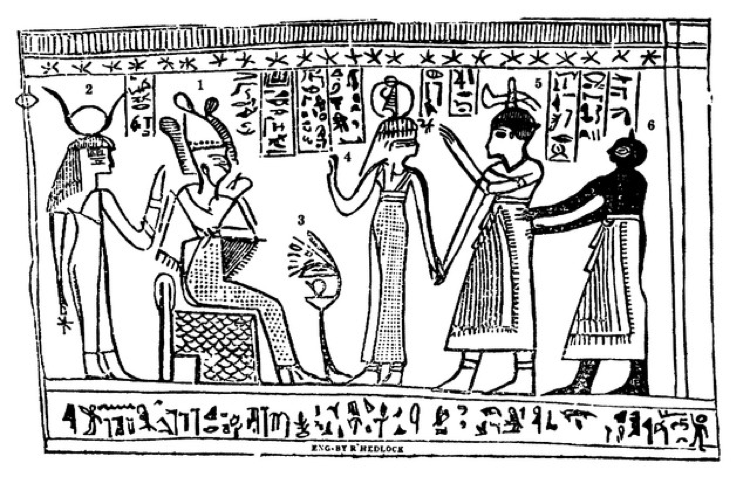

- Abraham being knowledgeable about astronomy and teaching such to the Egyptians2

For example, an early Christian author named Eusebius preserved an account of Abraham teaching the Egyptians astronomy: “Abraham lived in Heliopolis with the Egyptian priests and taught them much: He explained astrology and the other sciences to them, saying that the Babylonians and he himself had obtained this knowledge.”3 The ancient Jewish historian Josephus likewise recorded that Abraham taught the Egyptians astronomy: “He communicated to them arithmetic, and delivered to them the science of astronomy; for, before Abram came into Egypt, they were unacquainted with those parts of learning.”4

Another recurring theme in these ancient extra-biblical accounts about Abraham is his having a vision of the cosmos and being brought into the presence of God.5 Medieval Jewish sources also speak of Abraham having in his possession a “glowing precious stone” with which he read the stars and performed miracles:

Abraham wore a glowing stone around his neck. Some say that it was a pearl, others that it was a jewel. The light emitted by that jewel was like the light of the sun, illuminating the entire world. Abraham used that stone as an astrolabe to study the motion of the stars, and with its help he became a master astrologer. For his power of reading the stars, Abraham was much sought after by the potentates of East and West. So too did that glowing precious stone bring immediate healing to any sick person who looked into it. At the moment when Abraham took leave of this world, the precious stone raised itself and flew up to heaven. God took it and hung it on the wheel of the sun.6

With a few exceptions, the extra-biblical sources discussing Abraham that parallel the account in the Book of Abraham were unavailable to Joseph Smith. Even with those sources that could have been available to the him, such as the writings of Josephus, it is not clear how much exposure or access Joseph Smith had to them or how much they influenced his thinking.7 “Josephus was known to Oliver Cowdery and theoretically known to Joseph Smith, but it is not clear that Joseph Smith actually read much, if anything, out of Josephus before he translated the Book of Abraham. While some elements of the Book of Abraham agree with Josephus, there are important disagreements as well.”8

It is also important to keep in mind that these later sources do not necessarily always reflect an accurate history of Abraham’s life. “Not all [ancient] authors treated their sources [about Abraham] the same way. Some authors retold the tales they read in their own words, adding more vivid and imaginative details. Other authors repeated their sources word for word. Some authors expanded their stories, while others abbreviated them, and still others left them unchanged. This makes it difficult to come up with a general theory [for their reliability] that covers all cases.”9

What is important for the Book of Abraham is not that these sources somehow “prove” the book is true, which they don’t. Rather, they demonstrate that important themes and narrative details in the Book of Abraham fit comfortably in the ancient world and do not always fit comfortably in Joseph Smith’s nineteenth century environment.10 “The nonbiblical traditions about Abraham underscore the pervasive influence this great patriarch had on ancient and modern peoples. Because the Book of Abraham parallels so many nonbiblical stories, it is clearly part of the same tradition.”11

While they perhaps do not rise to the level of “proof,” these parallels are still evidence for the Book of Abraham because “it is difficult to argue that Joseph Smith wrote the Book of Abraham using [these] Abrahamic stories because most of them were not available to him, and those that were often contained details that do not match the Book of Abraham. On the other hand, the ancient existence of a Book of Abraham can explain why these stories existed.”12

Further Reading

Hugh Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2009), 375–468.

Hauglid, Brian M. “The Book of Abraham and Muslim Tradition,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 131–146.

John A. Tvedtnes, Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee, eds., Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2001).

Bradley J. Cook, “The Book of Abraham and the Islamic Qisas al-Anbiya (Tales of the Prophets) Extant Literature,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 33, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 127–146.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Abrahamic Lore in Support of the Book of Abraham,” FARMS Report (1999).

Footnotes

1 Hugh Nibley provided pioneering work on this subject. See Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2000), 11–42; An Approach to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2009), 375–468. More recently, John A. Tvedtnes, Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee have collected and synthesized a large (though not exhaustive) amount of these sources. See John A. Tvedtnes, Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee eds., Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2001). See additionally Bradley J. Cook, “The Book of Abraham and the Islamic Qisas al-Anbiya (Tales of the Prophets) Extant Literature,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 33, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 127–146; Brian M. Hauglid, “On the Early Life of Abraham: Biblical and Qur’anic Intertextuality and the Anticipation of Muhammad,” in Bible and Qur’an: Essays in Scriptural Intertextuality, ed. John C. Reeves (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003), 87–105; “The Book of Abraham and Muslim Tradition,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 131–146.

2 Tvedtnes, Hauglid, and Gee, Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham, 537–547.

3 Tvedtnes, Hauglid, and Gee, Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham, 8–9.

4 Tvedtnes, Hauglid, and Gee, Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham, 49.

5 Jared W. Ludlow, “Abraham’s Visions of the Heavens,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005), 57–73.

6 Howard Schwartz, Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2004), 332, citing B. Bava Batra 16b; Zohar 1:11a-11b, Idra Rabbah. As Schwartz comments, “This talmudic legend about a glowing stone that Abraham wore around his neck is a part of the chain of legends about that glowing jewel, known as the Tzohar, which was first given to Adam and Eve when they were expelled from the Garden of Eden and also came into the possession of Noah, who hung it in the ark. See The Tzohar, p. 85. This version of the legend adds the detail that the glowing stone was also an astrolabe, with which Abraham could study the stars.”

7 Lincoln H. Blumell, “Palmyra and Jerusalem: Joseph Smith’s Scriptural Texts and the Writings of Flavius Josephus,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 356–406, esp. 371–373.

8 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2017), 159.

9 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 158.

10 See the discussion in Andrew W. Hedges, “A Wanderer in a Strange Land: Abraham in America, 1800–1850,” in Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, 175–187.

11 Tvedtnes, Hauglid, and Gee, Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham, xxxv.

12 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 160.