Book of Moses Essay #6

Moses 6:15, 37–68; 7:2, 13, 38

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

As Enoch set out to fulfill his prophetic commission, it seems that his preaching at first attracted listeners only because of its value as local entertainment. Everyone was eager to see the noisy religious fanatic:

And they came forth to hear him, upon the high places, saying unto the tent-keepers:1 Tarry ye here and keep the tents, while we go yonder to behold the seer, for he prophesieth, and there is a strange thing in the land; a wild man hath come among us. (Moses 6:38, emphasis added)

The rare term “wild man” fairly pops out at the reader. It is used only once elsewhere in scripture, as part of Jacob’s prophecy about how Ishmael will live to become everyone’s favorite enemy.2 However, a much more interesting parallel to the Book of Moses can be found in the Book of Giants —an Aramaic Enoch manuscript discovered at Qumran. To fully appreciate the significance of what this small detail adds to the larger Enoch story, some background will be helpful.

Holy and Unholy Wild Men

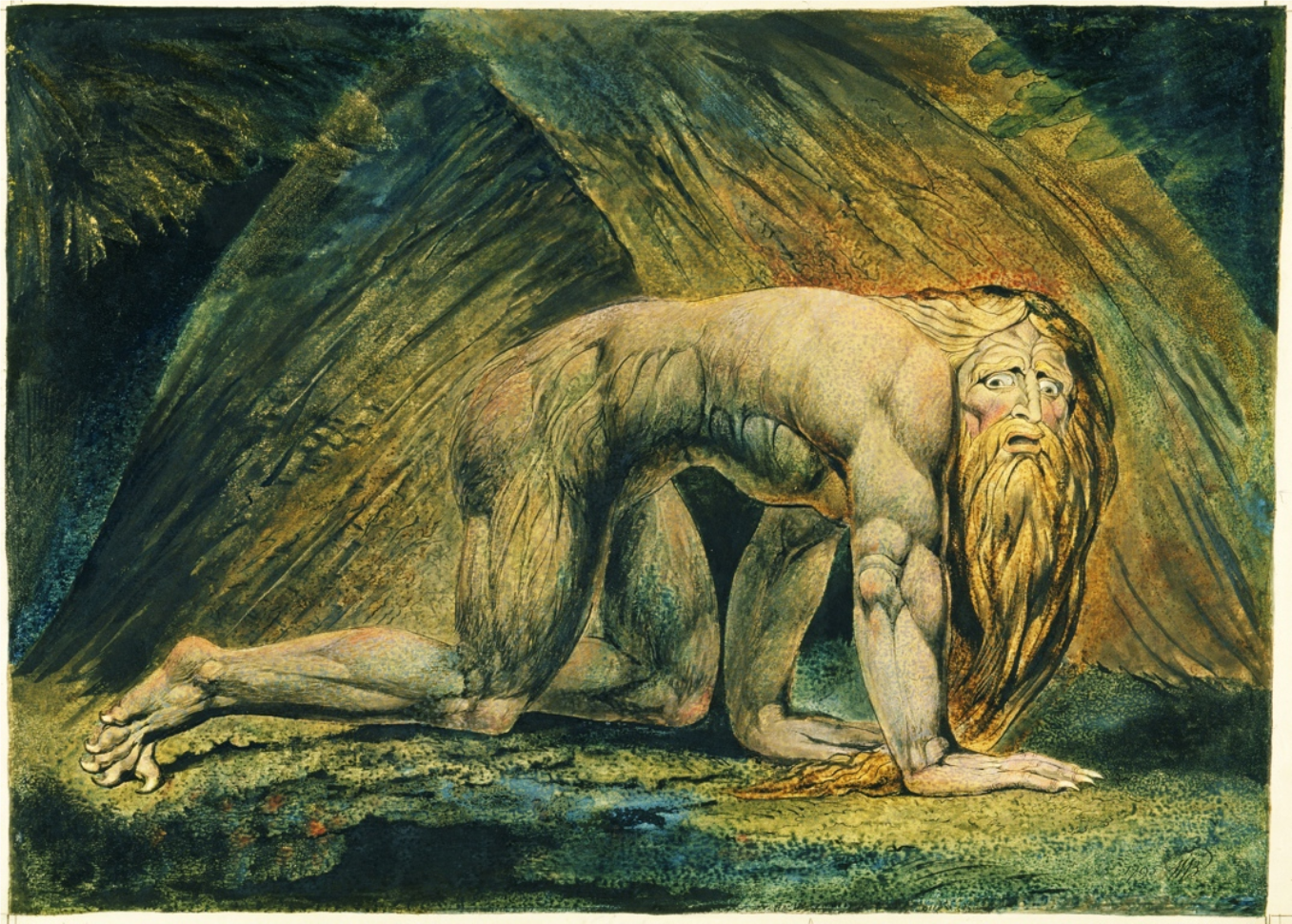

The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar is the best-known biblical type of a “wild man.” After spurning the Lord’s call to repentance, his fate was announced by the prophet Daniel:3

O king Nebuchadnezzar, … The kingdom is departed from thee. And they shall drive thee from men, and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field … until thou know that the most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will. The same hour was the thing fulfilled upon Nebuchadnezzar: and he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws.

In William Blake’s grotesque depiction of Nebuchadnezzar shown above, “we see [the king] in exile, animal-like on all fours. Naked, he gazes with mad horror at his own reflection like some kind of anti-Narcissus.”4

Seeking to characterize the typological “children of Nebuchadnezzar” in sacred and secular literature, Penelope Doob contrasted the literary convention of the “unholy wild man” with that of the “holy wild man.”5 Nebuchadnezzar is the prototype of the former category, his madness and self-exclusion from society ending only when he satisfactorily completed the process of penance.6 Other “wild men” in the Bible who, by way of contrast to Nebuchadnezzar, never lost their “wildness” include Ishmael,7 Esau,8 Samson,9 and the archetypal forebear of the biblical gibborim, Nimrod.10 Of interest in tracing the history of these characters is that they often served as “the secondary, wild counterpart to the primary hero”11 —Ishmael vs. Isaac, Esau vs. Jacob, Nimrod vs. Abraham,12 or perhaps even the “wild and savage”13 Lamanites vs. the Nephites.

In its single appearance in scripture outside of the story of Enoch, the term “wild man” (used in the King James Bible for Ishmael) translates the literal Hebrew “wild-ass man,” calling to mind:14

the sturdy, fearless, and fleet-footed Syrian onager (Hebrew pere’), who inhabits the wilderness and is almost impossible to domesticate. Jeremiah describes the wild ass of the desert: “snuffing the wind in her eagerness, whose passions none can restrain.”15 Hagar … will produce a people free and undisciplined.

The description of Ishmael as an “onager man” matches that of Enkidu as akkanu (onager) in the old Babylonian epic Gilgamesh, an indomitable warrior whose prowess was proved in bloody battle: a “wild ass on the run, donkey of the uplands, panther of the wild”16 who “slaughtered the Bull of Heaven” and “killed Humbaba.”17

On the other hand, Adam,18 Elijah,19 John the Baptist,20 and later Christian practitioners of monasticism and asceticism are sometimes identified as exemplars of the “holy wild man,” though it is important to point out that they are never actually called that in scripture.21 These figures voluntarily took on their rough clothing as “fools for God”22 in a quest for “greater knowledge.”23 The single luxury afforded by the spartan lifestyle of these “prophets in the wilderness,”24 was the freedom to dedicate themselves single-mindedly to the preaching of repentance with a loud voice to spiritually deaf hearers.25

Was Enoch a Wild Man?

Enoch was certainly not an “unholy wild man.” But does he actually fit the description of a “holy wild man”? Two ways of answering this question present themselves. The first option is quite simple and obvious. The second is more complex and speculative but may offer a more complete explanation of what little relevant information we have in scripture. In order to adequately discuss both options, this Essay will be a little longer than usual.

Option 1: Enoch was a “holy wild man,” somewhat of the same mold as John the Baptist. In certain respects, Enoch seems to fit the bill of a “holy wild man” when we compare him with John the Baptist. Like Enoch, John the Baptist drew crowds who had more interest in seeing some “strange thing”26 than in hearing their entrenched beliefs challenged. The Book of Moses account paints the people addressed by Enoch as spiritual cousins to Paul’s Athenian audience who “spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing.”27 Had Enoch’s appearance been a trivial, commonplace event, a mere “reed shaken in the wind,”28 they would have just stayed home to begin with—as unchanged as they were when they returned home after hearing him. Surely, as the account implies, such individuals would not have left their tents simply “to gaze upon an everyday sight,” 29especially when, as with John, they would have had to travel to “the hills and high places”30 to find him.

In addition to whatever else we might infer in a speculative mood about the Enoch’s appearance being a “strange thing in the land,”31 the Book of Moses itself gives us an explicit example of what piqued people’s interest in going to see Enoch — namely, because “he prophesieth.”32 Does this mean, perhaps, that “the word of the Lord was precious [i.e., rare] in those days; there was no open vision”?33 If so, the very scarcity of prophets and prophecy may also help explain Enoch’s appeal as a local novelty.34

Whatever factors might have established Enoch as a strange and rare spectacle, the Book of Moses goes on to reveal that he was a formidable source of fright:35

when they heard him, no man laid hands on him; for fear came on all them that heard him.

Later, when warfare erupted with Enoch’s followers, his power over natural elements when speaking “the word of the Lord” provoked fear throughout the entire region:36

And so great was the faith of Enoch that he led the people of God, and their enemies came to battle against them; and he spake the word of the Lord, and the earth trembled, and the mountains fled, even according to his command; and the rivers of water were turned out of their course; and the roar of the lions was heard out of the wilderness; and all nations feared greatly, so powerful was the word of Enoch, and so great was the power of the language which God had given him.

To sum up, Enoch’s rare appearance as an outsider and a formidable prophet, perhaps a sort of proto-Samuel the Lamanite,37 preaching a disruptive message in the wilderness at a time when prophets may have been scarce, when combined with the fearful power over nature and his enemies that God had given him may have been sufficient reason for the people to have describe him as a “wild man.”38

Option 2: Enoch was not a “wild man,” but was simply called one in mockery. Apart from the description of Enoch’s dominance in battle (to which we will return below), the direct evidence from scripture indicates only that Enoch shared certain aspects of John’s “strangeness.” But are there strong indications in the Book of Moses39 that Enoch also shared the key identifiers of John’s “wildness”—for example, his rough apparel, his social isolation, and his rigorous diet? Surprisingly, we do not find enough evidence in scripture to make us wholly confident that Enoch embodied the essential qualities of the “wild man” typology that seem to have been prevalent in his day.

To situate Enoch’s audience more precisely, we turn from the later examples of Elijah and John the Baptist to the older and more pointedly relevant literature that illustrates the concept of “wild man” in times closer to the life of Enoch. Several useful studies of recurring appearances and echoes of various peoples that were called gibborim (Hebrew “mighty warriors”40) may help us understand older meanings of the term “wild man” and the social setting of Enoch’s mission from the perspective of Jewish tradition.

The Hebrew word gibbor itself gives us a starting point. “Etymologically, with its doubled middle consonant,” writes Gregory Mobley, “gibbor is an intensive form of geber, ‘man.’ In this regard, as masculinity squared, gibbor roughly compares to the English compound ‘he-man.’”41 And in what manly qualities was a gibbor expected to excel? Brian R. Doak summarizes a relevant aspect of his sociolinguistic analysis of the culture of the gibborim in biblical times as follows:42

As human-like embodiments of that which is wild and untamed, the biblical [gibbor] takes on the role of “wild man,” “freak,” and “elite adversary” for heroic displays of fighting prowess.

If the cultural values hinted at in the Book of Giants and similar literature about the gibborim bear any resemblance to those of Enoch’s audience in the Book of Moses—and certainly the brief but highly revealing description of merciless ethnic warfare described Moses 7:5–10 provides some support for this hypothesis43—the personal quality most admired among the gibborim was indeed “fighting prowess.” We might infer that the greatest compliment that one gibbor could pay to another would be to acknowledge his standing as a veritable “wild man.”

In the Enoch literature inside and outside of scripture, how does Enoch measure up to how a gibbor might describe a “wild man”? Did he ever revel in the wild thrill of human slaughter? Had he ever slain a lion with his bare hands?44 Did he have any reputation at all as a bow-man or a hunter? For that matter, was he said to have been “large in stature,”45 like Nephi and Mormon, Book of Mormon prophets who later became military leaders? When we look for any match between descriptions of Enoch and the core traits of a “wild man” in the biblical tradition (and more especially in the gibborim culture), we come up empty-handed.

If we grant that Enoch is not explicitly said to have the core qualities and experiences that would have clearly marked him as a “wild man,” why then would anyone have called him one?46 That is the puzzle.

So we start at the beginning: What do we know about the character of Enoch from the Book of Moses at the time of his call? Since we know very little, what little we know from scripture becomes important. And from what Robert Alter, the eminent scholar of the literary aspects of the Old Testament, tells us about the way biblical narrative works, “at the beginning of any new story, the point at which dialogue first emerges will be worthy of special attention, and in most instances, the initial words spoken by a personage will be revelatory, … constituting an important moment in the exposition of character.”47

What did Enoch say at that moment? He “bowed himself to the earth” — and then humbly expounded his unfitness for the task: “I … am but a lad, and all the people hate me; for I am slow of speech.”48 “With a few deft strokes the [scriptural] author, together with the imagination of his reader, constructs a picture that is more ‘real’ than if he had drawn it in detail.”49 Enoch’s words have provided what Laurence Turner calls an “announcement of plot.”50 Thus, as readers, we are now equipped with clues about what we should be looking for as the story proceeds.

Indeed, Enoch’s first statement is especially telling: “I … am but a lad.”51 In a warrior culture, a “lad” (Hebrew na‘ar) occupies the lowest rung on the ladder of respect. To the gibbor to whom fighting was everything, the inexperienced na‘ar was a nothing. Mobley explains:52

A na‘ar … can mean many things—“boy,” “servant,” “assistant,” “infantryman”—but in every case is less than a gibbor. To the superior party, a veteran warrior, there was no glory in fighting below his station. Goliath disdains the na‘ar David, who emerges from the Israelite camp to face him.53

Then, once Enoch begins to preach, we are led to ask: If Enoch’s own people hated him, and plausibly mocked him for being “slow in speech,” why would his enemies have been any more charitable to him when he first made his appearance? Would hostile locals who had only heard rumors about Enoch be prone to speak glowingly of his anticipated oratory style, stature, or prowess? Or is it more likely that they would continue the sort of mockery to which Enoch had been accustomed back home? Moreover, it should be observed that any initial prejudice against Enoch’s appearance and delivery was apparently magnified by the content and severity of the message itself: he “cried with a loud voice, testifying against their works; and all men were offended because of him.”54

Another important clue to understanding the changing attitudes of the people toward Enoch is found in verses 38 and 39. These verses seem to be deliberately contrastive, revealing the difference in the attitude of the crowd before and after they heard Enoch. In verse 38, before the people “came forth … to behold the seer,” they mentioned to the “tent-keepers”—perhaps in a sarcastic or derisive manner—that “a wild man hath come among us.”55 It seems that only after Enoch opened his mouth to his hearers is their mocking tone replaced by an awestruck attitude: “When they heard him, no man laid hands on him; for fear came on all them that heard him.”56

By the time we reach the end of the story, we realize that Enoch’s initial self-characterization as being “slow in speech” has prepared us for the ironic turning of the tables that plays out on a larger stage in his final military victory. This may constitute one of the primary lessons of the account: namely, that Enoch conquered his foes through the “virtue of the word of God.”57 In contrast to the gibborim, aspiring wild men who “conquered according to [their] strength,”58 Enoch, who lacked any of the macho qualities his enemies held dear, won his battles as “he spake the word of the Lord.”59 His former weakness had become his strength60 through “the power of the language which God had given him.”61 And the physical strength of the gibborim was, crushingly, nothing but weakness when facing Enoch, a divinely empowered adversary.62

Consistent with the moral of such a lesson, later biblical authors pointedly taught that “Israel’s future did not lie along”63 the “way [of] all [their] warriors [gibborim],”64 but rather in “turn[ing] back to the Lord with all [one’s] heart.”65 Proverbs 24:25 averred that “A wise man is mightier than a strong one.”66 Paraphrasing, we might understand this to mean that the “wise man” is more of a geber67 than the gibbor — in other words, the “wise man” is more of a “man” than the “he man.” Similarly, the preacher of Ecclesiastes 9:16 concluded that “wisdom (ḥokmâ) is superior to [“manly”] heroism (gĕbûrâ).”68

Is there a precedent in the Book of Moses for the incident that attached in mockery the incongruous label of “wild man” to Enoch? Yes, one can find the same style of rude humor in Moses 8, where a reversal of labels was used to please the party-goers in Noah’s day. As the drunken crowd of “sons of men”69 who had spurned Noah’s preaching70 and married his granddaughters71 filled and refilled their wine cups, they laughingly called themselves the “sons of God.”72 At the same time, after playfully exalting their own status, they sarcastically called their wives “daughters of men,”73 deliberately deprecating the lineage of their wives as daughters of the sons of Noah. Significantly, these sons of Noah, the fathers of these wives, had been specifically characterized as “the sons of God.”74 Though the labels vary, the tasteless and worn-out brand of humor remains the same in every generation.

Daffy Duck: “Precisely what I was wondering, my little Nimrod.”

Continuing with a modern example, we suggest that the term “wild man” might have been used sarcastically by the gibborim to mock the relatively smaller stature of Enoch when compared to themselves, perhaps similar to the case of Daffy Duck calling the hopelessly inept hunter Elmer Fudd “my little Nimrod.”75

What about the “Wild Man” in the Book of Giants?

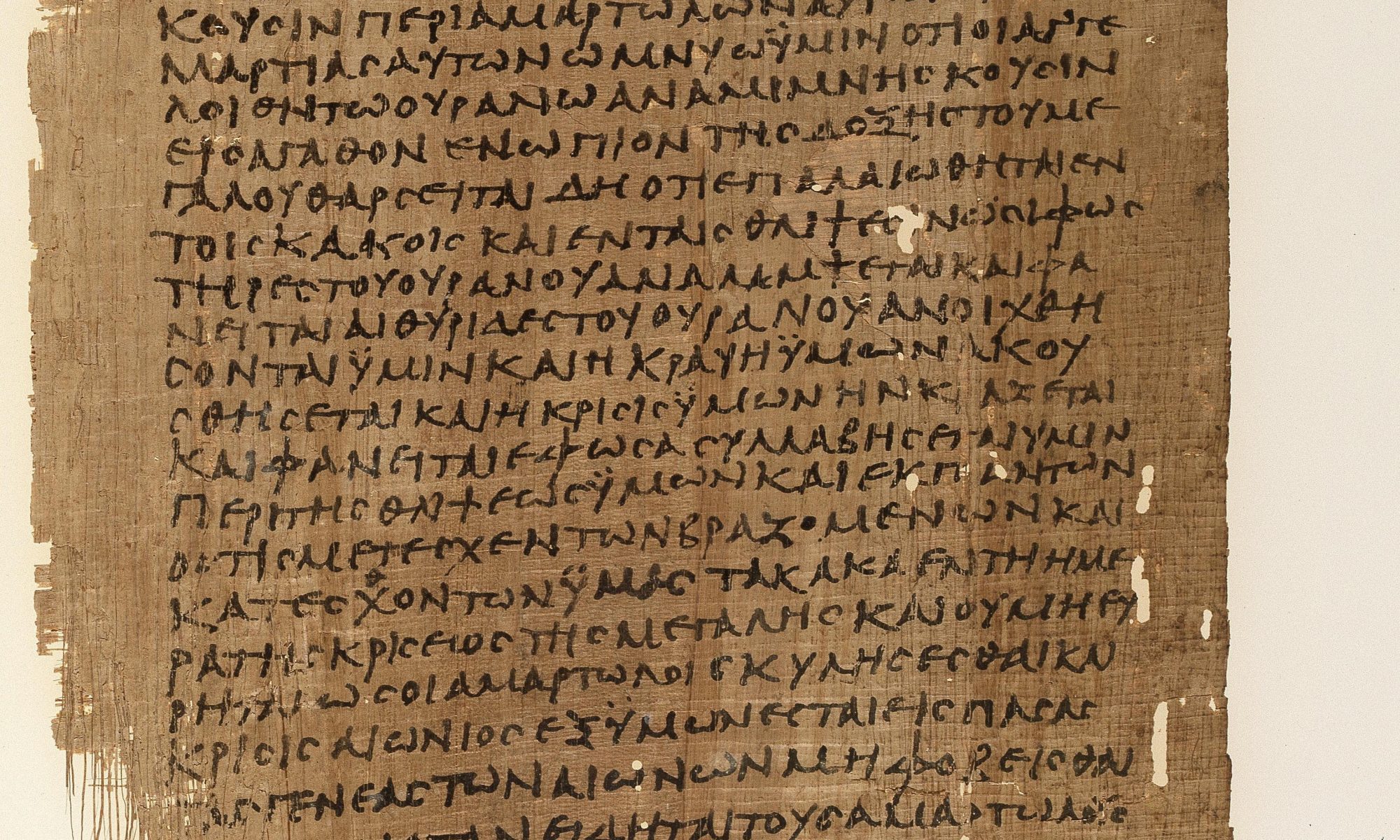

As to the “wild man” who appears in the Aramaic Enoch tradition from Qumran, it should first be noted that past scholars have sometimes doubted that the term “wild man” even appears in the Book of Giants. However, while earlier Book of Giants translations of the relevant passage sometimes contained either one or the other but not both of the terms “wild man” and “wild beasts,” there is an increasingly solid consensus that both terms are present in the original manuscript.76

If the growing consensus is correct, one of the wicked leaders of the gibborim, perhaps Gilgamesh,77 called himself “the wild man.” We draw on the translation of Edwin Cook to provide background for the statement of the wicked gibbor as an admission of his humiliating defeat and resulting personal debasement by Enoch and his people:78

3. [ … I am] mighty, and by the mighty strength of my arm and my own great strength

4. [and I went up against a]ll flesh, and I made war against them; but I did not

5. [prevail, and I am not] able to stand firm against them, for my opponents

6. [are angels who] reside in [heav]en, and they dwell in the holy places [ … ] And they were not

7. [defeated, for they] are stronger than I. [ … ]

8. [ ] of the wild beast has come, and the wild man they call [me.]

Joseph Angel ably compares the humbling of the arrogant leader of the gibborim, muttering to himself in dismay after his defeat, to the principal theme of the story of Nebuchadnezzar. Angel perceptively recognizes that the characterization of both Nebuchadnezzar and Gilgamesh as “wild men both appear to be related to the Epic of Gilgamesh.”79 In this dramatic turn of events, the would-be mighty wild man (in the proud tradition of the gibborim) is literally or figuratively transformed into a beastly wild man of Mesopotamian and biblical tragedy.80 The reader of the account will also see, in line with the typical biblical “wild man” tradition, that Enoch’s enemy has played “the secondary, wild counterpart to the primary hero”81—who, in both the Book of Giants and the Book of Moses, is clearly Enoch himself.

Conclusion

The Book of Moses and the Book of Giants are two different works, published millennia apart, each with a unique past and their own story to tell. That said, whatever the exact meaning of the term “wild man” in these two accounts may be, the fact that this rare and peculiar description shows up in these already closely related stories about Enoch hints that they may each contain shards of a common, pre-existing literary tradition. So far as we are able to determine, the single occurrence of the term “wild man” in the extant ancient Enoch literature is in the Book of Giants and the only instance of it in the scripture translations of Joseph Smith is in the Enoch account in the Book of Moses.

This article was adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 42, 68.

Further Reading

Angel, Joseph L. “The humbling of the arrogant and the ‘wild man’ and ‘tree stump’ traditions in the Book of Giants and Daniel 4.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck, and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 61–80. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 42, 68 (“wild man”), 84, 203, 225 (sons of men and daughters of Noah).

Doak, Brian R. “The giant in a thousand years: Tracing narratives of gigantism in the Hebrew Bible and beyond.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck, and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 13–32. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016, pp. 24–25.

Doob, Penelope B. R. Nebuchadnezzar’s Children: Conventions of Madness in Middle English Literature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 74 n. 45, 96 (“wild man” and “tent-keepers”), 161–164 (sons of men and daughters of Noah).

Mobley, Gregory. “The wild man in the Bible and the Ancient Near East.” Journal of Biblical Literature 116, no. 2 (1997): 217-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3266221. (accessed April 6, 2020).

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 180, 211–213.

References

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

—, ed. The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2019.

Angel, Joseph L. “The humbling of the arrogant and the “wild man” and “tree stump” traditions in the Book of Giants and Daniel 4.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 61-80. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Berlin, Adele. 1983. Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994. https://books.google.com/books?id=eLoBhPENIBQC. (accessed April 10, 2020).

Blake, William. The Illuminated Blake: William Blake’s Complete Illuminated Works with a Plate-by-Plate Commentary. New York City, NY: Dover Publications, 1974.

Bloom, Harold. 1963. Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

—. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

—. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Davies, W. D., and Dale C. Allison. 1991. The Gospel According to St. Matthew. 3 vols. The International Critical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, ed. J. A. Emerton, C. E. B. Cranfield and G. N. Stanton. London, England: T&T Clark, 2012.

de Troyes, Chrétien. ca. 1180. “Yvain.” In Arthurian Romances. Translated by W. W. Comfort, 157-233. Mineola, NY: Dover Books, 2006.

Doak, Brian R. “The giant in a thousand years: Tracing narratives of gigantism in the Hebrew Bible and beyond.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 13-32. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Doob, Penelope B. R. Nebuchadnezzar’s Children: Conventions of Madness in Middle English Literature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Eisler, Robert. The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist According to Flavius Josephus’ Recently Rediscovered ‘Capture of Jerusalem’ and the Other Jewish and Chrstian Sources (Shortened version of German edition published as ΙΗΣΟϒΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕϒΣ Οϒ ΒΑΣΙΛΕϒΣΑΣ: Messianische Unabhängigkeitsbewegung vom Auftreten Johannes des Täufers bis zum Untergang Jakobs des Gerechtenn ach der neuerschlossenen Eroberung von Jerusalem des Flavius Josephus und den christlichen Quellen, Religionswissenschaftliche Biliothek 9, 2 vols., Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung,1929-30). Translated by Alexander Haggerty Krappe. New York City, NY: Lincoln MacVeaagh, The Dial Press, 1931. http://www.christianjewishlibrary.org/PDF/LCJU_MessiahJesus.pdf. (accessed January 25, 2020).

Frye, Northrop. 1947. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969.

George, Andrew, ed. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London, England: The Penguin Group, 2003.

Laertius, Diogenes. 1925. “Solon.” In Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Books 1-5. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Translated by R. D. Hicks. The Loeb Classical Library 184, 46-69. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959. https://archive.org/details/DiogenesLaertius01LivesOfEminentPhilosophers15_201412. (accessed April 7, 2020).

Lidzbarski, Mark, ed. Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer. 2 vols. Giessen, Germany: Alfred Töpelmann, 1905, 1915.

—. Mandäische Liturgien. Berlin, Germany: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1920.

—, ed. Ginza: Der Schatz oder das Grosse Buch der Mandäer. Quellen der Religionsgeschichte, der Reihenfolge des Erscheinens 13:4. Göttingen and Leipzig, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, J. C. Hinrichs’sche, 1925. https://ia802305.us.archive.org/7/items/MN41563ucmf_2/MN41563ucmf_2.pdf. (accessed September 7, 2019).

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. “The Book of Giants (4Q531).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 262. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

MichaelK. In which cartoon (if any) did Bugs Bunny use the term “nimrod”? Movies & TV Stack Exchange, 2017. https://movies.stackexchange.com/questions/81453/in-which-cartoon-if-any-did-bugs-bunny-use-the-term-nimrod. (accessed February 22, 2020).

Migne, Jacques P. “Livre d’Adam.” In Dictionnaire des Apocryphes, ou, Collection de tous les livres Apocryphes relatifs a l’Ancien et au Nouveau Testament, pour la plupart, traduits en français, pour la première fois, sur les textes originaux, enrichie de préfaces, dissertations critiques, notes historiques, bibliographiques, géographiques et théologiques, edited by Jacques P. Migne. Migne, Jacques P. ed. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Troisième et Dernière Encyclopédie Théologique 23, 1-290. Paris, France: Migne, Jacques P., 1856. http://books.google.com/books?id=daUAAAAAMAAJ. (accessed October 17, 2012).

Milik, Józef Tadeusz, and Matthew Black, eds. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran Cave 4. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Mitchell, Stephen. Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York City, New York: Free Press, 2004.

Mobley, Gregory. “The wild man in the Bible and the Ancient Near East.” Journal of Biblical Literature 116, no. 2 (1997): 217-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3266221. (accessed April 6, 2020).

—. The Empty Men: The Heroic Tradition of Ancient Israel. The Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. David Noel Freedman. New York City, NY: Doubleday, 2005.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

—. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Parry, Donald W., and Emanuel Tov, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader. 6 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2005.

Pseudo-Clement. ca. 235-258. “Recognitions of Clement.” In The Ante-Nicene Fathers (The Writings of the Fathers Down to AD 325), edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. 10 vols. Vol. 8, 77-211. Buffalo, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1886. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Reeves, John C., and Annette Yoshiko Reed. Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2 vols. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. “Persecution of the prophets.” Nauvoo, IL: Times and Seasons 3, No. 21, 1 September 1842, 1842, 902-03. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/times-and-seasons-1-september-1842/8. (accessed May 2, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Andrew F. Ehat, and Lyndon W. Cook. The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph, 1980. https://rsc-legacy.byu.edu/out-print/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph. (accessed April 25, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Turner, Laurence. Announcements of Plot in Genesis. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 96, ed. David J. A. Clines and Philip R. Davies. Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1990. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/14343346.pdf. (accessed July 28, 2017).

Vaughan, Agnes Carr. Madness in Greek Thought and Custom. Baltimore, MD: J. H. Furst Company, 1919. https://books.google.com/books?id=RfnOAAAAMAAJ. (accessed April 7, 2020).

Widtsoe, John A. “Enoch, whom the Lord took unto himself.” The Juvenile Instructor 36, no. 11 (1 June 1901): 342-46. https://books.google.com/books?id=c6XtAAAAMAAJ. (accessed May 2, 2020).

William Blake Online: Blake’s Cast of Characters: Personification of the Fallen Tyrant. In Tate Gallery. http://www.tate.org.uk/learning/worksinfocus/blake/imagin/cast_04.html. (accessed April 27, 2007).

William Blake: Blake’s Cast of Characters. In Tate Gallery. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/william-blake-39/blakes-characters. (accessed May 2, 2020).

Zurski, Ken. 2020. The Nimrod effect: How a cartoon bunny changed the meaning of a word forever. In Unremembered History. https://unrememberedhistory.com/2017/01/09/the-nimrod-effect-how-a-cartoon-bunny-changed-the-meaning-of-a-word-forever/. (accessed February 26, 2020).

Footnotes

1 With regard to the tent-keepers, R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, p. 96 comment:

These people were evidently a servant class. In addition, the term may be a further indicator that Enoch was preaching among Cain’s people, for it was they who inaugurated a life of dwelling in tents (see Moses 5:45); moreover, the tasks of the tent-keeper apparently included watching over livestock (see ibid., p. 74 n. 45).

2 Genesis 16:12.

3 Daniel 4:31–33.

4 Blake Online, Blake Online. See also W. Blake, Illuminated Blake, p. 121; N. Frye, Symmetry, pp. 270-272. It has often been claimed that Blake himself struggled with madness. On the topic of Blake’s possible madness, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, p. 783. Blake’s image was painted in 1795. In France, Louis XVI had been executed two years before. “Meanwhile, in England, George III, whose control the American colonists had recently thrown off, suffered from bouts of insanity[—thus] this picture of a degraded king [could] be an expression of Blake’s sympathy for the republicans in France and America” (William Blake’s Cast, William Blake’s Cast). “In his outcry against the imposition of any code of uniformity upon contrary individualities,” Blake reminds society that “it tempts the fate of Nebuchadnezzar, a fall into dazed bestiality, if it will not heed the warnings of [the prophet’s transforming] vision” (H. Bloom, Blake’s Apocalypse, p. 96).

5 P. B. R. Doob, Nebuchadnezzar’s Children. We exclude from the present discussion additional individuals that some might class as “wild men,” but for different reasons. These might include David, who feigned madness to blunt reports that he was a threat to Achish the king of Gath (1 Samuel 21:12–15) and Solon, who needed a cover of madness to expound his illegal message (D. Laertius, Solon, pp. 46–51; A. C. Vaughan, Madness, p. 63). However, in scripture and the ancient world, “madness,” the domain of the “irrational,” was generally a different category than “wildness,” the domain of “otherness.” Describing this “otherness,” Gregory Mobley, following Richard Bernheimer, observed: “if the wild man is residing nearby, he is a demonic figure; if far away, a representative of a monstrous race; if far away in time, a prehistoric specimen” (G. Mobley, Wild Man, pp. 219–220).

6 Besides the scriptural example of Nebuchadnezzar, Doob includes in the former category the Arthurian knights Yvain, Lancelot, and Tristan, who were driven mad by disappointments in love. See, e.g., C. de Troyes, Yvain, p. 189, where Yvain “dwelt in the forest like a madman or a savage.” Thanks to BYU professor Jesse Hurlbut for this reference.

7 Of Ishmael, Mobley writes (G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 226): Ishmael’s early life is associated with the midbar (“wilderness,” Genesis 16:7, 21:14, 20, 21) … and gains renown as a bow-man.

8 Of Esau, Mobley writes (ibid., p. 226): Esau is called an ish sadeh (“man of the field,” Genesis 25:27) and an ish sair (“hairy man,” Genesis 27:11). This famous hunter even exudes the earthy aroma of nature (Genesis 27:27).

9 Of Samson, Mobley writes (ibid., p. 229):

Though the Bible does not say a word about body hair, Samson’s hair, uncut since birth, is his signal trait. Samson establishes his credentials as master of beasts in his inaugural feat of wrestling a lion (Judges 14:5–6) and later by capturing and controlling the foxes (Judges 15:4–5). … Samson sleeps in a rock crevice (15:8), and he eats wild honey (Judges 14:9–10) and drinks [neither wine nor beer] (Judges 13:4, 7, 14); that is, he eschews city food. Samson usually works without tools — he tears the lion apart and uproots the city gate of Gaza bare-handed (Judges 14:6; 16:3 — and when he does require a tool, it is drawn directly from the animal world, the jawbone of an ass (Judges 15:15).

Though Mobley also describes several important characteristics of Samson that are not typically associated with the Old Testament “wild man,” he asserts that Samson “cannot be understood … apart from the wild man tradition, both in its specific ancient Near Eastern manifestations and within the larger international horizon of its folkloric development” (ibid., p. 231).

10 For more on Nimrod, see Book of Moses Essay #12, forthcoming.

11 G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 228.

12 On Nimrod vs. Abraham, see J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, pp. 338, 350–352.

13 D&C 109:65.

14 N. M. Sarna, Genesis, p. 121 n. 12 a wild ass of a man.

15 Jeremiah 2:24.

16 A. George, Gilgamesh, Tablet 8, line 51, p. 65.

17 S. Mitchell, Gilgamesh, Book 8, p. 153.

18 G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 227. See also J. M. Bradshaw, Moses Temple Themes (2014), pp. 177–179.

19 G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 227 notes the literal Hebrew description of Elijah as “lord of hair” (2 Kings 1:8, vs. King James “man of hair”), a “frequenter of caves” (1 Kings 19:9) whose successor Elisha “sends bears to do his bidding” (2 Kings 2:23-24). He further observes: The epithets for Elijah and Esau, [“lord of hair” and “hairy man”], respectively, are the semantic equivalent of … laḫmu[, the carefully coiffed Akkadian type of the wild man (see ibid., pp. 223–224)].

20 Of John the Baptist, Mobley writes (ibid., p. 228):

John the Baptist lives in the wilderness, eats a primitive diet, wears animal skins, dies through the agency of a woman, and, above all, functions as the secondary, wild counterpart to the primary hero.

Ibid., p. 228 n. 49 further observes that ”the traditions about John explicitly compare him to Elijah (e.g., Matthew 17:9–13; Mark 9:11–13; Luke 1:17). John’s birth story (Luke 1:5-80) has parallels with the book of Judges’ and Pseudo-Philo’s versions of Samson’s birth.”

21 However, Joseph Smith did once call John the Baptist a “wild man of the woods” (J. Smith, Jr. et al., Words, James Burgess Notebook, 23 July 1843, p. 235). But it seems doubtful that this description was intended to match the Mandaean Ginza description of some of Enoch’s contemporaries, who were branded as as false prophets. Their appearance and behavior is characterized as follows (J. P. Migne, Livre d’Adam, pp. 17, 46, translation by Bradshaw. Cf. H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 212):

From there come corruptors who wander through the mountains and hills, completely naked like demons, with bristly hair. … We call them vagabond pastors. They feed themselves on the grasses of the field … and say to themselves: “God speaks in mysteries from our mouths.”

.By way of contrast, some Muslim traditions credit Enoch with the invention of sewing with cloth (perhaps a confusion of “the homophonic Arabic verbs khaṭṭa ‘write’ and khāṭa ‘sew’”), in contrast to earlier people who are said to have worn animal skins (J. C. Reeves et al., Enoch from Antiquity 1, pp. 104-107).

22 See 1 Corinthians 4:10.

23 Abraham 1:2.

24 See G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 227. Joseph Smith once said (J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 1 September 1842, p. 261. Cf. J. Smith, Jr., Persecution of the Prophets, p. 903):

It is a shame to the Saints to talk of chastisements, and transgressions, when all the Saints before them, prophets and apostles, have had to come up through great tribulation. … How many have had to wander in sheep skins and goat skins, and live in caves and dens of the mountains, because the world was unworthy of their society?

25 See H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 213.

26 Moses 6:38, emphasis added.

27 Acts 17:21.

28 Matthew 11:7.

29 W. D. Davies et al., Gospel According to Matthew, 2:247. Having written that, however, Davies and Allison admit that:

one should not … altogether exclude the possibility that Jesus or Matthew had something very different in mind. To one steeped in the Hebrew OT, the image of reeds blown by the wind might have recalled Exodus 14–15, where God sends forth a strong wind to drive back the Sea of Reeds. The meaning of Jesus’ query would then be: Did you go out into the wilderness to see a man repeat the wonders of the Exodus?

Given Enoch’s power over the elements (see Essay #4), such a miracle in his case would not have been impossible.

30 Moses 6:37.

31 Moses 6:38.

32 Moses 6:38, emphasis added.

33 1 Samuel 3:1.

34 Cf. J. A. Widtsoe, Enoch, p. 345), who wrote:

He prophesied many things of the future, and revealed the secrets of men’s hearts so plainly, that the people flocked about him in astonishment, saying that “there is a strange thing in the land; a wild man hath come among us.” In their ignorance and unbelief they could only think that the power of prophecy was the product of a crazy brain.

35 Moses 6:39.

36 Moses 7:13.

37 Helaman, chapters 13–15.

38 Moses 6:38.

39 Outside the Book of Moses, we currently find only one source that hints at such an affinity. If one takes the Enosh referred to in relevant passages of the Mandaean Ginza to be based upon traditions about Enoch as is clear in certain other places in the Ginza (see Essay #4), the following summary of Lidzbarski’s conclusions by Robert Eisler (very briefly translated and paraphrased in H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 212) may bear on the possibility of traditions that saw John the Baptist as “Enosh/Enoch reborn” in fulfillment of Daniel’s prophecy of the coming of “one like unto the son of man” (R. Eisler, Messiah Jesus, pp. 231–232):

It may appear strange that Josephus does not know the Baptist’s name and speaks of him only as the “wild man” (’ish sadeh [literally “man of the field”]). But the explanation is surprisingly simple; it is given by the Baptist’s elusive answer, as quoted by the historian [i.e., Josephus, in the Slavic version of his account], to the question as to who he is: celovek esmi, “I am a man and as such (hither) has the spirit of God called me.” The Baptist therefore replied, ’Enosh ’ani, “I am ‘Enosh,’” i.e., simply “man,” just as Jesus called himself Bar nasha (cf. the Mandaean Bar-’Anosh = Adam, M. Lidzbarski, Ginza, p. 118 n. 14) the “Son of Man,” or simply “the man.” This explains at last how the Mandaeans, i.e., the Nasoraeans of Mesopotamia (see, e.g., M. Lidzbarski, Johannesbuch, p. 243; M. Lidzbarski, Liturgien, pp. 10ff., 25ff.; M. Lidzbarski, Ginza, pp. 29, 32, 47, 55), arrived at their peculiar doctrine, namely that Enosh reappeared in Jerusalem at the same time as ’Ishu Mshiha, Jesus Christ. The latter they are wont to call the “liar” or “impostor” (ibid., pp. 49ff) because he posed as a worker of miracles whom, however, Enosh unmasked. In all these transactions Enosh appears in a cloud, wherein he dwells or conceals himself and wherefrom at need he makes for himself the semblance of a body, walking thus on earth in human form (ibid., pp. 29, 199ff.). It has long since been recognized that this cloud has its origin in Daniel’s version, “there came with (or ‘on’) the clouds of heaven one like unto a son of man” (Daniel 7:13). From all this it would appear that there must have existed a fierce rivalry between the disciples of the Baptist and those of Jesus who belonged to this particular circle. The inference might long ago have been drawn from the passage in the Fourth Gospel on the Baptist as the “forerunner” of the Messiah, inasmuch as the “wild man” throughout regards himself not as the forerunner of someone greater, but as the “reborn Enosh” foretold in Daniel’s vision, i.e., as the Messiah. At any rate, he was so regarded by his disciples (Pseudo-Clement, Recognitions, 1:54, p. 92; 1:60, p. 93. Cf. Luke 3:15).

40 See the discussion of the Hebrew term gibborim in Book of Moses Essay #5. In the context of the Book of Giants, it is arguably better understood as “mighty warrior” than “giant.”

41 G. Mobley, Empty Men, p. 35.

42 B. R. Doak, Giant in a Thousand Years, p. 24.

43 See H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, pp. 281–282.

44 Judges 14:5–6.

45 1 Nephi 2:16; 4:31; Mormon 2:1.

46 Moses 6:38.

47 R. Alter, Narrative, p. 74.

48 Moses 6:31.

49 A. Berlin, Poetics, p. 137, speaking of the conventions of biblical narrative.

50 See L. Turner, Announcements, pp. 13-14. An “announcement of plot” is not a description of what is happening at the moment in the narrative, but rather a brief anticipatory summary of the principal events of the story that follows. Turner gives the book of Genesis as an example (ibid., pp. 13-14):

Each of the four major narrative blocks which comprise the book (i.e., the primaeval history and the stories of Abraham, Jacob, and Jacob’s family) is prefaced by statements which either explicitly state what will happen, or which suggest to the reader what the major elements of the plot are likely to be. Thus the initial divine command to humans in 1:28 sets out in a brief compass what human beings are supposed to do, and it is a natural question for the reader to ask whether in fact what is expected to happen actually does happen. … While passages which drop clues concerning plot development are interspersed throughout the Genesis stories, it is significant that statements which have an explicitly programmatic purpose are set right at the beginning of narrative cycles. …

Because the Announcements cause the reader to expect the plot to develop in certain ways, one key consideration will be the fate of the individual Announcements. Does the plot in fact develop as the Announcement leads us to believe? If so, in what way, and if not, in what way and why not?

51 For more on Enoch as a “lad,” see Pearl of Great Price Central, “Enoch’s Prophetic Commission: Enoch As a Lad,” Book of Moses Essay #3 (May 15, 2020).

52 G. Mobley, Empty Men, p. 51.

53 See the relationship between Enoch and David as “lads” described in Essay #3 endnote 2.

54 Moses 6:37.

55 Moses 6:38.

56 Moses 6:39.

57 Alma 31:5. Note that the word “virtue” is a term whose older meaning connotes strength, especially strength in battle. It comes from the Latin nominative virtus (= valor, merit, moral perfection), which derives from the root vir (= man).

58 Alma 30:17.

59 Moses 7:13.

60 See Ether 12:27.

61 Moses 7:13.

62 Sss G. Mobley, Empty Men, pp. 59–68 for a description of how inspiration, fear, and courage functioned as heroic conventions.

63 Ibid., p. 2.

64 R. Alter, Hebrew Bible, Hosea 10:13, 2:1230–1231.

65 Ibid., 2 Kings 23:25, 2:606.

66 Ibid., Proverbs 24:5, 3:426.

67 G. Mobley, Empty Men, p. 3 uses the phrase “more the geber.”

68 Ibid., p. 4.

69 Moses 8:14.

70 Moses 8:20.

71 Moses 8:13–14.

72 Moses 8:21.

73 Moses 8:21.

74 Moses 8:13. For more on this episode, see J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, pp. 84, 203, 225; J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 53–65. Cf. H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 180.

75 For more on Nimrod as a “wild man” and the defeat of the gibborim, see Book of Moses Essay #12, forthcoming. See “What Makes Daffy Duck (1947),” at about 5:35. For a history of how the name of the biblical “mighty hunter” Nimrod (Genesis 10:9) became a synonym for an inept person, see K. Zurski, Nimrod Effect. Zurski seems to be mistaken about Bugs Bunny using the term “nimrod” to describe Elmer Fudd (MichaelK, In Which Cartoon), even though several websites claim he did it in “A Wild Hare” (1940). However in a cartoon called “Rabbit Every Monday” (1951) Bugs calls Yosemite Sam “the little nimrod” (at about 6:53).

76 See the discussion in J. L. Angel, Humbling, pp. 66–68. For an earlier discussion of translation difficulties in this passage, see L. T. Stuckenbruck, Book of Giants, p. 163. Edward Cook’s “preferable” (J. L. Angel, Humbling, p. 67) translation is: “[ ] of the wild beast has come, and the wild man they call [me]” (Edward Cook, “4Q531 (4QEnGiants(c) ar),” 22:8 in D. W. Parry et al., Reader, 3:495). Others, going further than Stuckenbruck’s more conservative reading of “rh of the beasts of the field is coming” (L. T. Stuckenbruck, Book of Giants, p. 164), understand the phrase as “the roar of the wild beasts has come” (F. G. Martinez, Book of Giants (4Q531), 22:8, 262) or “the roaring of the wild beasts came” (J. T. Milik et al., Enoch, p. 208).

77 See J. L. Angel, Humbling, pp. 67–68.

78 Edward Cook, “4Q531 (4QEnGiants(c) ar),” 22:3–8 in D. W. Parry et al., Reader, 3:495. For a rationale that gives credit for the defeat of the gibborim to Enoch and his people, see Essay #24.

79 J. L. Angel, Humbling, p. 68. Angel continues:

The portrayal of Gilgamesh roaming like a wild man after the death of Enkidu is a well-known image from the Mesopotamian epic. And, as Matthias Henze has pointed out, Daniel’s portrait of Nebuchadnezzar as [having become] a wild man is best understood as a polemical reversal of Enkidu’s metamorphosis portrayed in Gilgamesh.

80 See J. L. Angel, Humbling, p. 68.

81 G. Mobley, Wild Man, p. 228.