Joseph Smith–History Insight #18

One of the more dramatic divine pronouncements delivered to Joseph Smith during his First Vision concerns the creeds being propounded by Christian leaders and theologians of his day. Upon asking the two glorious personages—God the Father and Jesus Christ—which of the Christian denominations he should join, Joseph recorded the following answer in his 1838–39 account of the vision:

I was answered that I must join none of them, for they were all wrong; and the Personage who addressed me said that all their creeds were an abomination in his sight; that those professors were all corrupt; that: “they draw near to me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me, they teach for doctrines the commandments of men, having a form of godliness, but they deny the power thereof.” (Joseph Smith–History 1:19)

This is, by any standard, a direct and harsh reply. It is also consistent with the accounts left by Joseph before and after this one. In his 1832 account of the vision, Joseph reported that the Lord told him, “Behold, the world lieth in sin at this time, and none doeth good, no, not one. They have turned aside from the gospel and keep not my commandments. They draw near to me with their lips while their hearts are far from me.”1 Later in 1842, in a statement that seems to have been carefully worded to lessen any offence to its intended public audience, Joseph paraphrased what he learned from the heavenly personages thus: “They told me that all religious denominations were believing in incorrect doctrines and that none of them was acknowledged of God as his church and kingdom.”2

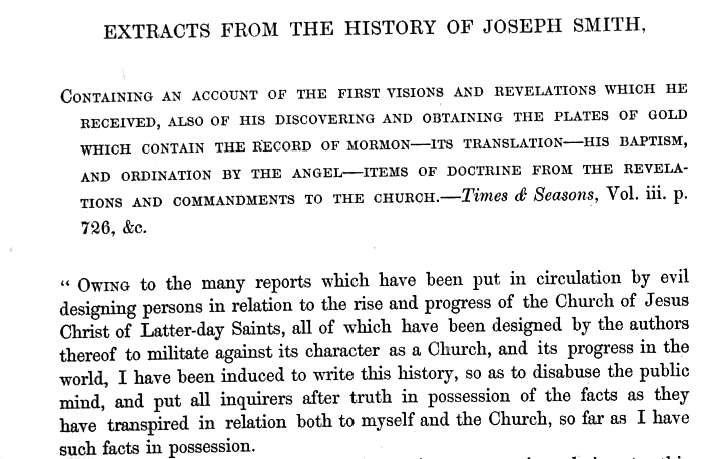

In order to assess the intention behind the language of the 1838–39 account that spoke of the Christian creeds being an “abomination,” a number of considerations need to be kept in mind. The first is the historical setting of the composition of this account. As historian Steven Harper has noted, Joseph Smith composed his 1838 history at a time when he and other Latter-day Saints were experiencing bitter persecution. The troubles of the Kirtland apostasy of 1837 and mounting tensions that would lead to the outbreak of the Missouri War of 1838 undoubtedly influenced the defensive tone of this history.3 Little wonder that Joseph began his account refuting what he deemed “many reports which have been put in circulation by evil-disposed and designing persons, in relation to the rise and progress of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, all of which have been designed by the authors thereof to militate against its character as a Church and its progress in the world” (Joseph Smith–History 1:1).

This context also explains why the theme of Joseph’s boyhood persecution as a consequence to him telling others about the First Vision is prominent in this narrative (Joseph Smith–History 1:21–26), an element that goes underplayed or omitted from his other accounts of the First Vision. Keeping in mind that the 1838 account has Joseph paraphrasing what the Lord told him, it therefore seems likely that the harsher tone of this account was deliberate on Joseph’s part. “In [Joseph] Smith’s 1839 present, persecution dominated his past,” writes Harper.

He had triumphed over mobs and militias, and now he made sense of his present position as the embattled president of a new church. The combination of Smith’s past and present consolidated a defensive, resolute memory in which reporting his first vision catalyzed his lifetime of persecution. . . . [The 1838–39 account of the First Vision] shapes [Latter-day Saints’] identity as a people persecuted from transcending creedal Christianity and accessing God directly.4

Beyond the setting and tone of the 1838 account is the consideration of what creeds specifically Joseph may have had in mind with this account. After all, over the many centuries of Christian history, hundreds of creeds have been issued by orthodox Christians of different theological traditions. Are there particularly problematic creeds that Joseph perhaps had in mind? Deriving from the Latin credo, meaning “I believe,” a creed, at its most basic definition, is “a statement of the shared beliefs of (an often religious) community in the form of a fixed formula summarizing core tenets.”5 Latter-day Saints, who affirm that as a result of the Great Apostasy many important points of the pure doctrine of Jesus Christ were distorted or lost, have traditionally been very suspicious of and even sometimes outrightly hostile towards the orthodox creeds of Christendom, viewing them as the product of a time when revelation was not guiding the formulations of perhaps sincere but still misguided churchmen.6

Sometimes it’s the content of the creed that riles Latter-day Saints, such as in the case with the Westminster Confession of 1647, which affirms: “There is but one only living and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts, or passions, immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible . . .”7 This formulation of the nature of God runs directly at odds with the Latter-day Saint belief in an embodied God who is knowable through revelation and certainly not immutable, without passions (Doctrine and Covenants 130:22–23; Moses 7:26–31). More often, however, it is what creeds represent than what they contain that makes Latter-day Saints uneasy. As Joseph Smith himself remarked: “I cannot believe in any of the creeds of the different denominations because they all have some things in them [that] I cannot subscribe to, though all of them have some truth. But I want to come up into the presence of God and learn all things; but the creeds set up stakes and say ‘hitherto shalt thou come, and no further’ — which I cannot subscribe to.”8 For the Prophet, creeds were an impediment to receiving new light and knowledge from God because they needlessly constricted believers into narrow boxes of dogma. As he said on another occasion: “[T]he most prominent point of difference in sentiment between the Latter-day Saints and sectarians [is] that the latter [are] all circumscribed by some peculiar creed, which deprived its members the privilege of believing anything not contained therein; whereas the Latter-day Saints have no creed, but are ready to believe all true principles that exist, as they are made manifest from time to time.”9

In addition to all of this, scholar John W. Welch has pointed out that the multitudinous creeds of Protestant Christianity that were written and circulated during the three centuries leading up to Joseph’s lifetime led to increased “protest and confusion” as believers atomized into increasingly niche subgroups.10 Whereas the creedal statements in the New Testament were personal statements of testimony, and the main creeds of the early Christian councils were institutional statements internally defining orthodoxy,11 beginning in the Reformation,

Creeds now became statements of belief, formulated for the purpose of distinguishing and differentiating one religious group from another. Into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the number of creeds climbed and the verbosity and complexity of these confessions soared. While all of this positioning may have been understandably necessitated by the political and rational forces that surrounded the various Protestant denominations or sects, the result was precisely as Joseph’s experience depicts. Confusion, dissension, and self-serving manipulation characterized much of the religious fervor of his day, erupting in many cases (not only against the Mormons) in hostility, persecution, and violence.12

“By 1820,” Welch continues, “numerous creeds of various denominations had been brought into existence,” with no sign of slowing down.13 With their often highly polemical language and stridently contentious aims, the formulation of many of the creeds Joseph would have been reacting against coincided not only with the bloody wars of religion fought in Europe, but also with the “the tumultuous times of the First and Second Awakenings in the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries” in North America.14 It was precisely because of these creeds that Joseph grew up in a religious environment “of great confusion and bad feeling[s],” with “priest contending against priest, and convert against convert; so that all their good feelings one for another, if they ever had any, were entirely lost in a strife of words and a contest about opinions” (Joseph Smith–History 1:6). Inasmuch as Jesus himself proclaimed that contention and disputation was of the devil (3 Nephi 11:29), there can be little doubt as to why Jesus would have expressed regret and dismay at the way creeds were being utilized by competing and intransigent ministers and professors of religion in Joseph’s day.

The stark language of the 1838 account of the First Vision which denounces the creeds as “abominations” forces readers to make a decision about the ultimate truthfulness of Joseph Smith’s visionary claims.15 At the same time, however, most Latter-day Saints, while concurring with the negative assessment of creedal Christianity in the Prophet’s account, are eager to approach this subject judiciously and with the same kind of fair-mindedness they ask of other Christians for their beliefs. Latter-day Saints should be careful not to misrepresent or misconstrue what the orthodox creeds actually say,16 much less use them as a bludgeon to attack sincere Christians of either Catholic or Protestant backgrounds. Although Joseph Smith was highly critical of the Christian creeds, he was also sensitive to the fact that they do contain many things that are true, which the Saints readily recognize and welcome into their own religious paradigms where appropriate.17

Further Reading

John W. Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’:A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Provo, UT and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2004), 228–249.

Roger R. Keller, “Christianity,” in Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions, ed. Roger R. Keller (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 230–267.

Joseph Fielding McConkie, “The First Vision and Religious Tolerance,” in A Witness for the Restoration: Essays in Honor of Robert J. Matthews, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Andrew C. Skinner (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 177–199.

Footnotes

1 History, circa Summer 1832, 3, spelling standardized.

2 “Church History,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 707.

3 Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 13–21. See additionally Alexander L. Baugh, “Joseph Smith in Northern Missouri, 1838,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Religious Studies Center, 2010), 291–346.

4 Harper, First Vision, 18–19.

5 “Creed,” online at Wikipedia.org.

6 For representative examples of the traditional Latter-day Saint approach to the Great Apostasy, see B. H. Roberts, Outlines of Ecclesiastical History (Salt Lake City, UT: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1893); James E. Talmage, The Great Apostasy (Salt Lake City, UT: The Deseret News, 1909). These older works, which are outdated in many regards on historical points, have been supplanted in popularity and utility more recently by Noel B. Reynolds, ed., Early Christians in Disarray: Contemporary LDS Perspectives on the Christian Apostasy (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005); Scott R. Petersen, Where Have All the Prophets Gone? Revelation and Rebellion in the Old Testament and the Christian World (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2005); Tad R. Callister, The Inevitable Apostasy and the Promised Restoration (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2006). For a recent academic treatment on the concept of apostasy in the Latter-day Saint tradition, see Standing Apart: Mormon Historical Consciousness and the Concept of Apostasy (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).

7 The Westminster Confession of Faith (II.I), in Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom (New York, NY: Harper, 1877), 3:606.

8 Discourse, 15 October 1843, as Reported by Willard Richards, [pp. 128–129], spelling standardized.

9 History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843], p. 1433, spelling standardized. See generally, Gary P. Gillum, “Creeds,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (MacMillan: New York, 1992), 1:343.

10 John W. Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’:A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Provo, UT and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2004), 240.

11 For a chart comparing the texts of seven main Post-Apostolic Creeds, see “The Post-Apostolic Creeds,” in John W. Welch and John F. Hall, eds., Charting the New Testament (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2002).

12 Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’,” 240.

13 Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’,” 240.

14 Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’,” 244.

15 See the thoughts in Joseph Fielding McConkie “The First Vision and Religious Tolerance,” in A Witness for the Restoration: Essays in Honor of Robert J. Matthews, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Andrew C. Skinner (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 177–199.

16 For an exemplary Latter-day Saint approach to the Nicene Creed—which is a target in popular and often misinformed Latter-day Saint polemics—see Lincoln Blumell, “Rereading the Council if Nicaea and Its Creed,” in Standing Apart, 196–217. In this piece, Blumell engages with the Nicene Creed carefully and thoughtfully, articulating rightful points of critique while also acknowledging areas of agreement between it and Latter-day Saint theology. See also his interview with Laura Harris Hales in “Episode 112: The Council of Nicaea and Its Creed with Lincoln H. Blumell,” online at LDS Perspectives Podcast.

17 Discourse, 23 July 1843, as Reported by Willard Richards, p. 14, transcribed in History, 1838–1856, volume E-1 [1 July 1843–30 April 1844], p. 1681, thus: “Have the Presbyterians any truth? Yes. Have the Baptists, Methodists &c. any truth? Yes, they all have a little truth mixed with error. We should gather all the good and true principles in the world and treasure them up or we shall not come out pure Mormons.” See further Terryl Givens, “‘We Have Only the Old Things’: Rethinking Mormon Restoration,” in Standing Apart, 335–342; Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015), 23–41.