Book of Moses Essay#2

Moses 6:31–32, 35

With contribution by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw

The Opening of Enoch’s Mouth

When the Lord called Enoch as a prophet, Enoch was concerned about his ability to adequately preach to the people. In particular, he described himself as being “slow of speech.”1 Moses may have been quoting Enoch when, after receiving his own prophetic calling, he told the Lord he was “slow of speech, and of a slow tongue”2 —literally, in Hebrew idiom, “heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue.”3

In Moses’ case, as with Ezekiel, the problem was most likely not a physical speech impediment,4 but rather doubts about his fluency in the native language of his hearers.5 What language would that be? Not Egyptian, of course, because Moses had been raised in Egypt6 and during his first appearance at Pharaoh’s court both he and Aaron did the speaking.7 Rather, as Richard E. Friedman argues, Moses more likely had difficulty with Hebrew. Friedman observes that “God’s response in fact confirms that the problem for Moses was speaking ‘to the people,’8 not to the Egyptians.”9

Could Enoch have been in a similar predicament? After all, he was not sent to preach repentance to his own people (who presumably spoke his own language), but rather to the people in the eastern land where his journey had taken him.10 Whatever the case, non-canonical Enoch sources seem to corroborate that Enoch had speech challenges. Some accounts, for example, portray Enoch as having been “deliberate in his speech” and “often silent.”11

These descriptions are notable because being “slow of speech” is not a common motif among biblical prophets. Only Moses and Enoch are specifically described in this manner. It is also curious that in the cases of both Enoch and Moses, “it is the stammerer whose task it is to bring down God’s word to the human world.”12 “Whatever the circumstances, the underlying idea is that prophetic eloquence is not a native talent but a divine endowment granted for a special purpose, the message originating with God and not with the prophet.”13

Although God provided Aaron as a spokesman for Moses, He offered no such relief to Enoch. Instead, He gave Enoch himself “the power of … language”14 —a term that is found nowhere else in scripture. By this power and at his “command” in speaking “the word of the Lord, … the earth trembled, and the mountains fled, … and the rivers of water were turned out of their course; and the roar of the lions was heard out of the wilderness,” causing “all nations [to fear] greatly.”15

The wording of God’s promise to Enoch is also significant:16 “Open thy mouth, and it shall be filled, and I will give thee utterance.” Again, the most obvious parallel is in the call of Moses, to whom the Lord declared: “I will be with thy mouth, and teach thee what thou shalt say.”17 However, a similarly close parallel is found in pseudepigraphal Enoch literature. In 2 Enoch 39:5, Enoch states: “… it is not from my own lips that I am reporting to you today, but from the lips of the Lord I have been sent to you. For you hear my words, out of my lips, a human being created exactly equal to yourselves; but I have heard from the fiery lips of the Lord.”18

Commenting on Old Testament language that mentions the enabling of a prophet’s “lips,” “tongue,” and “mouth,” biblical scholar Carol Meyers found meaningful “parallels in the empowering ‘opening the mouth’ rituals in ancient Near Eastern texts, especially Egyptian ones.”19 Hugh Nibley recalled that “one purpose of the Egyptian Opening of the Mouth is to cause the initiate ‘to remember what he had forgotten—that it is to awaken the mind to its full potential in the manner of the awakening of Adam in a new world.”20 By rites of this sort, the mouth is also sanctified21 and becomes a conduit for the transmission of heavenly things.

Nibley further explained:22

The rite is called the Opening of the Mouth because that must come first, that being the organ by which one may breathe, receive nourishment, and speak. … So the mouth comes first; but to rise above mere vegetation, life must become conscious and aware, so that the opening of the eyes immediately follows.

The Opening of Enoch’s Eyes

Moses 6:35–36 recounts the anointing, washing, and “opening” of Enoch’s eyes:

35 And the Lord spake unto Enoch, and said unto him: Anoint thine eyes with clay, and wash them, and thou shalt see.23 And he did so.

36 And he beheld the spirits that God had created; and he beheld also things which were not visible to the natural eye; and from thenceforth came the saying abroad in the land: A seer hath the Lord raised up unto his people.

Descriptions of Enoch’s visions or tours of the heavenly worlds appear frequently in pseudepigraphal texts. Though Enoch’s account in the Book of Moses focuses more on salvation history than on the fantastic celestial realms so prominent in other accounts, it is notable that what few details are given us in the Book of Moses often line up quite well with non-canonical accounts of his visions. For example, the Book of Moses prominently highlights Enoch’s ability to see “things which were not visible to the natural eye,” consistent with the Lord’s command in 2 Enoch for him to make a “record of all His creation, visible and invisible”24 and of his having seen God make “invisible things descend visibly.”25 Another account tells of how Enoch “trained” himself to see divine visions of invisible things while “in his normal (i.e., bodily) state.”26

| Moses 6:36 | 2 Enoch 64:5 | Sefer Mishkqn |

| [Enoch] beheld things which were not visible to the natural eye | And [the Lord] commanded Enoch to [make a] … record of all His creation, visible and invisible | Those … are not visible to anyone corporeal … but after [Enoch] trained himself to be with God, he saw (them) |

As a sign of their prophetic calling, the lips of Isaiah27 and Jeremiah28 were touched to prepare them for their roles as divine spokesmen. However, in the case of both the book of Moses and the pseudepigrapha, Enoch’s eyes “were opened by God”29 to enable “the vision of the Holy One and of heaven.”30 The words of a divinely given song recorded in Joseph Smith’s Revelation Book 2 are in remarkable agreement with 1 Enoch:31

| Song of Enoch 4 | 1 Enoch 1:2 |

| [God] touched [Enoch’s] eyes and he saw heaven | Enoch[‘s] … eyes were opened by God, who had the vision of the Holy One and of heaven |

This divine action would have had special meaning to Joseph Smith, who alluded elsewhere to instances in which God touched his eyes before the heavens were opened to him.32

The description of the anointing of the eyes with clay in the Book of Moses recalls the healing by Jesus of the man born blind.33 And, indeed, it may be that Jesus’ actions were meant, at least in part, to allude to the experience of Enoch. Further elucidating the meaning of this action, Craig Keener34 observed that “by making clay of the spittle35 and applying it to eyes blind from birth, Jesus symbolically repeated the creative act of Genesis 2:7.”36 Interestingly, in the Book of Moses, the first thing Enoch sees after having his eyes anointed with clay are the “spirits that God had created.”37

This article was adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 36, 39-41.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 36, 39–41, 93.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 94–95.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, p. 211.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 164–182 (The Opening of the Mouth Rite: Its Purpose and Origin).

References

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Bradley, Don. The Lost 116 Pages: Reconsructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2019.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. 2018. How Might We Interpret the Dense Temple-Related Symbolism of the Prophet’s Heavenly Vision in Isaiah 6? In Interpreter Foundation Old Testament KnoWhy JBOTL36A.

Bruce, F. F. The Book of Acts (Revised). Revised ed. The New International Commentary on the New Testament, ed. Gordon D. Fee. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988.

Buber, Martin. 1958. Moses: The Revelation and the Covenant. New York City, NY: Humanity Books, 1988.

Carasik, Michael, ed. The JPS Miqra’ot Gedolot: Exodus. The Commentator’s Bible. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 2005.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Evening and Morning Star. Independence, MO and Kirtland, OH, 1832-1834. Reprint, Basel Switzerland: Eugene Wagner, 2 vols., 1969.

Fox, Everett, ed. The Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. The Schocken Bible: Volume I. New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1995.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Friedman, Richard Elliott, ed. Commentary on the Torah. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2001.

Glazov, Gregory Y. Bridling of the Tongue and the Opening of the Mouth in Biblical Prophecy. JSOTS 311. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Kaiser, Walter C., Jr. “Exodus.” In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelein, 287-497. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990.

Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of John: A Commentary. 2 vols. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2003.

Magness, Jodi. “The impurity of oil and spit among the Qumran sectarians.” In With Letters of Light: Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish Apocalypticism, Magic, and Mysticism, edited by Daphna V. Arbel and Andrei A. Orlov. Ekstasis: Religious Experience from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, ed. John R. Levison, 223-31. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, 2011.

Meyers, Carol. Exodus. The New Cambridge Bible Commentary, ed. Ben Witherington, III. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Reeves, John C., and Annette Yoshiko Reed. Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2 vols. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Sandmel, Samuel, M. Jack Suggs, and Arnold J. Tkacik, eds. The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Exodus. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper. Manuscript Revelation Books, Facsimile Edition. The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin and Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2009.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen. Joseph Smith Histories, 1832-1844. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories 1, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin and Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2012.

Walker, Charles Lowell. Diary of Charles Lowell Walker. 2 vols, ed. A. Karl Larson and Katharine Miles Larson. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1980.

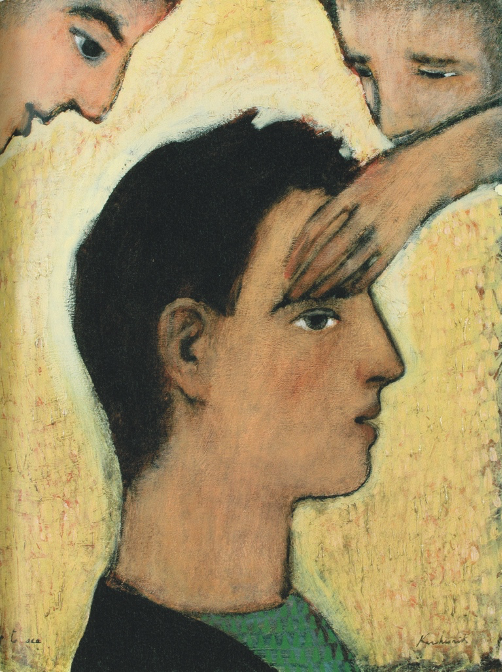

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Copyright Brian Kershisnik.

Figure 2. From the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, British Museum. Wikipedia.

Footnotes

1 Moses 6:31.

2 Exodus 4:10.

3 Cf. Exodus 6:30: “uncircumcised lips.”

4 As argued in some strands of Jewish tradition, e.g., Abarbanel, Nahmanides, Exodus Rabbah (M. Carasik, Exodus, p. 26; H. Freedman et al., Midrash, Exodus 1:26, 3:33–34). Contra RASHBAM: “We see in Ezekiel 3:5–6 that ‘slow of tongue’ describes one who is not fluent in the language of the realm. Could one possibly think that a prophet who knew God face to face, and received the Torah directly from His hand, was a stutterer? The idea that Moses stuttered is not found anywhere in rabbinic literature. Pay no attention to apocryphal books.” (M. Carasik, Exodus, p. 26). Note Stephen’s declaration in Acts 7:22 that Moses was “mighty in words” meaning “a powerful speaker” (S. Sandmel et al., New English Bible, Acts 7:22, p. 149). Cf. F. F. Bruce, Book of Acts, p. 139 n. 43; W. C. Kaiser, Jr., Exodus, p. 328 n. 10.

5 As Friedman points out (R. E. Friedman, Commentary, p. 181 n. 4:10):

“Heavy of tongue” occurs in one other place, Ezekiel 3:5–7. There YHWH [Jehovah] tells Ezekiel that he is not being sent to peoples who are “deep of lip and heavy of tongue,” whose words Ezekiel cannot understand. YHWH says, ironically, that such peoples would listen, but the house of Israel will not listen! In that context, “heavy of tongue” refers to nations who speak foreign languages. Cf. W. C. Kaiser, Jr., Exodus, p. 328 n. 10.

6 See Exodus 2.

7 Exodus 5:1, 3.

8 Exodus 4:16.

9 R. E. Friedman, Commentary, p. 181 n. 4:10.

10 Remember that when Enoch was called to preach and prophesy (see Moses 6:23), he was on a “journey out of the land of Cainan, the land of [his] fathers, a land of righteousness unto this day” (Moses 6:41, emphasis added). Thus “the people” (Moses 6:26) among whom he traveled and to whom he was called to preach repentance were in a different land.

11 J. C. Reeves et al., Enoch from Antiquity 1, p. 148. Perhaps also related is Wahb b. Munabbih’s report that Enoch “was soft-spoken and gentle in his manner of speaking.” J. C. Reeves et al., Enoch from Antiquity 1, p. 130.

12 E. Fox, Books of Moses, 1:277 n. 10, citing M. Buber, Moses.

13 N. M. Sarna, Exodus, p. 21 n. 10.

14 Moses 7:13.

15 Moses 7:13.

16 Moses 6:32.

17 Exodus 4:12.

18 F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, 39:5 (longer recension), p. 162.

19 C. Meyers, Exodus, p. 61, citing G. Y. Glazov, Bridling of the Tongue, pp. 361–383. More generally on the “opening of the mouth” in Egyptian, Jewish, and Christian tradition, see H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), pp. 164–182.

20 H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 176.

21 See Isaiah 6:5–7. For more about Isaiah’s vision, see J. M. Bradshaw, How Might We Interpret.

22 H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 179.

23 Cf. John 9:6–7.

24 F. I. Andersen, 2 Enoch, 64:5 [J], p. 190.

25 Ibid., 25:1 [J], p. 144.

26 R. Moses de León, Sefer Mishkan ha-‘Edut (ed. Bar-Asher), quoted in J. C. Reeves et al., Enoch from Antiquity 1, p. 321.

27 See Isaiah 6:5–7.

28 Jeremiah 1:9.

29 G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 1:2, p. 137. Cf. D&C 110:1: “the eyes of our understanding were opened.”

30 G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 1:2, p. 137.

31 J. Smith, Jr. et al., Manuscript Revelation Books, Facsimile Edition, Revelation Book 2, 48 [verso], 27 February 1833, pp. 508–509, spelling and punctuation modernized. See also J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, Excursus 2: The Song of Enoch, p. 449 v. 4; p. 452, v. 7. According to the “Song of Enoch,” the event occurred just prior to Enoch’s vision in Moses 7:4–11. Cf. “With finger end God touch’d his eyes” (E & MS, E & MS, 1:12 [May 1833]); Abraham 3:11–12. See J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, Endnote M6-8, p. 93.

32 Joseph Smith’s eyes were apparently touched at the beginning of the First Vision, and perhaps also prior to receiving D&C 76 (J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, Endnote M6-9, pp. 93–94). Andrew F. Ehat (personal communication) has suggested that, in accounts where the appearance of the Father preceded the appearance of the Son (see, e.g., J. Smith, Jr. et al., Histories, 1832–1844, p. 13 n. 45), it was specifically so that the Father could first touch the Prophet’s eyes, thus “open[ing] the heavens upon [him]” (ibid., History, circa summer 1832, p. 12) which enabled him to see the Savior (C. L. Walker, Diary, 2 February 1893, 2:755–756). See also D. Bradley, Lost 116 Pages, pp. 45, 203–204, 230–231, 234–239, 255–256 for insightful discussions of other significant events involving the touch of the finger of God.

33 John 9:6–7. See R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, p. 95.

34 C. S. Keener, John, 1:780.

35 Note that “the spit of certain people such as the zab and gentile was considered impure and presumably was avoided by Jews who were scrupulous in the observance of purity” (J. Magness, Impurity, p. 231).

36 Cf. John 20:22. This provides a fitting analog to the spiritual rebirth of Enoch, which in the Book of Moses is symbolized and actualized by the opening of his mouth and his eyes.

37 Moses 6:36; emphasis added. In verse 63 of this same chapter, the Creation—and its connection to Enoch’s new ability to see both physical and spiritual things—is emphasized even more pointedly: “And behold, all things have their likeness, and all things are created and made to bear record of me, both things which are temporal, and things which are spiritual; things which are in the heavens above, and things which are on the earth, and things which are in the earth, and things which are under the earth, both above and beneath: all things bear record of me.”