Book of Abraham Insight #39

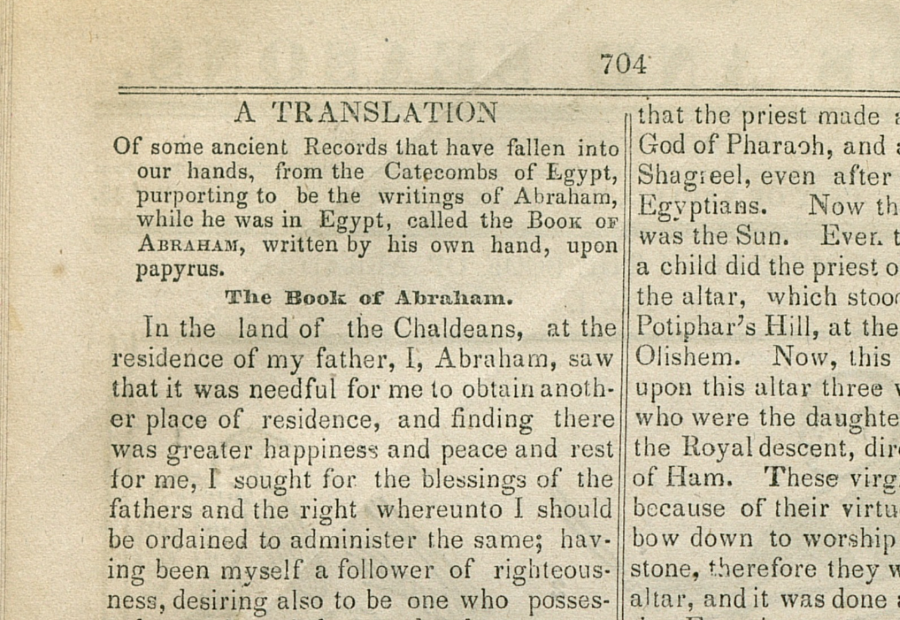

Multiple sources associated with the coming forth of the Book of Abraham spoke of Joseph Smith as translating the text.1 The Prophet himself used this language to describe his own activity with the text. For example, an entry in Joseph Smith’s journal under the date November 20, 1835 indicates the Prophet “spent the day in translating” the Egyptian records.2 In an unpublished editorial that was apparently meant to be printed in the March 1, 1842 issue of the Times and Seasons (the issue that saw the publication of the first installment of the Book of Abraham), Joseph Smith signaled his desire to “continue to translate and publish [the text] as fast as possible [until] the whole is completed.”3 What was published with the Book of Abraham was a preface announcing it as “A TRANSLATION Of some ancient Records that have fallen into our hands . . . purporting to be the writings of Abraham.”4

But while Joseph Smith and others used the word “translation” to describe the production of the Book of Abraham, the means or methods Joseph used to translate ancient scripture were unique. Rather than utilizing dictionaries, grammar books, and lexicons, Joseph translated scripture through revelation. This can be seen in the other efforts Joseph Smith undertook throughout his prophetic ministry to produce other books of scripture.5

The Book of Mormon

Joseph Smith’s signature work of scripture is the Book of Mormon, which the Prophet claimed to have translated from golden plates “by the gift and power of God.”6 While early efforts to decipher the “reformed Egyptian” (Mormon 9:32) characters of the Book of Mormon evidently did involve some mental effort by the Prophet and his scribes,7 ultimately the translation was accomplished through the use of divinely-prepared seer stones. “When Joseph Smith began translating the Book of Mormon in 1827, he usually left the plates in a box or wrapped in a cloth, placed the interpreters or his seer stone (both of which seem to have been called Urim and Thummim) in a hat, and read the translation he saw in the stone to a scribe. . . . When the first 116 pages of the Book of Mormon were stolen, an angel took back the interpreters, and Joseph instead used his seer stone.”8 All of this suggests that Joseph Smith’s mechanism for translating the Book of Mormon, while still in some way conveying one language (Egyptian) to another (English), was more closely synonymous with revelation.9

The Parchment of John (Doctrine and Covenants 7)

Doctrine and Covenants 7 was received by Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in April 1829 just before or during the time when Oliver acted as a scribe for the translation of the Book of Mormon.10 When this section was first published in 1833, it was described as “a Revelation [sic] given to Joseph and Oliver” and was said to have been “translated from parchment, written and hid up by” a figure named John (presumably the beloved disciple).11 This revealed “translation” of John’s record was received, like the Book of Mormon, through seeric instruments (the Urim and Thummim).12 It is important to remember that during this process Joseph Smith “did not have physical possession of the papyrus he was translating.”13

The “New Translation” of the Bible

Another important effort undertaken by Joseph Smith was what he called a “new translation” of the Bible.14 Accomplished principally between 1830–1833, this “new translation” of the Bible (today called the Joseph Smith Translation) was not accomplished by the Prophet carefully scrutinizing Hebrew and Greek manuscripts, nor even by consulting his seer stone or the Urim and Thummim, but instead by revising the English text of the King James Version of the Bible.15 “At the beginning of this translation, Joseph Smith would dictate long passages to his scribe without the use of the Urim and Thummim. When Sidney Rigdon began serving as a scribe, however, he apparently persuaded Joseph to change his practice and mark only passages in the Bible that needed changes and record those.”16 Even though Joseph and his clerks were revising the English text of the KJV and sometimes revealing entirely new content (such as portions of what is today called the Book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price),17 they nevertheless called the project a translation. While it is arguable that a handful of Joseph Smith’s revisions to the KJV Bible are indeed more precise renderings of the underlying Greek and Hebrew, or that the larger portions revealed by the Prophet in some way correspond to now-lost ancient manuscripts, this once again indicates the broad range of meaning the Prophet applied to this term.

The Book of Abraham

When it comes to the nature of the translation of the Book of Abraham, there is not much direct evidence for how Joseph accomplished the work. “No known first-person account from Joseph Smith exists to explain the translation of the Book of Abraham, and the scribes who worked on the project and others who claimed knowledge of the process provided only vague or general reminiscences.”18 John Whitmer, then acting as the Church’s historian and recorder, commented that “Joseph the Seer saw these Record[s] and by the revelation of Jesus Christ could translate these records … which when all translated will be a pleasing history and of great value to the saints.”19 Another important source is Warren Parrish, one of the scribes who assisted Joseph in the production of the Book of Abraham. After his disaffection from the Church in 1837, Parrish reported that in his capacity as Joseph’s scribe he “penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks as [Joseph] claimed to receive it by direct inspiration from Heaven.”20 Parrish’s statement, like Whitmer’s, emphasizes that the method of Joseph’s “translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks” was revelatory, not academic, but that the Prophet was still performing a translation of an ancient language. Unfortunately, Parrish did not elaborate further on the precise nature of this translation “by direct inspiration.”

Other sources report that the Prophet used the Urim and Thummim (meaning probably one of his seer stones) in the translation of the Book of Abraham, although these sources come from those not immediately involved in the production of the text, and in one instance may have been confusing the translation process of the Book of Abraham with the translation process of the Book of Mormon, and so they should be accepted cautiously.21 If Joseph did use a seer stone in the translation of the Book of Abraham, this would reinforce the point that the method or means of translation for the Prophet was unique.

Clues from the Book of Abraham text itself suggests that the Prophet felt free to continually adapt and revise his initial translation. For example, some of the names of the characters in the Book of Abraham were revised in 1842 shortly before the publication of the Book of Abraham.22 Likewise, Joseph Smith’s study of Hebrew appears to have also influenced the final form of the text, as Joseph’s knowledge of such influenced either how he initially rendered or later revised certain words and phrases in the Book of Abraham’s creation account.23 One of the glosses at the beginning of the book (“which signifies hieroglyphics”; Abraham 1:14) is not present in the Kirtland-era manuscripts, which appears to indicate that it came from Joseph Smith or one of his scribes at the time of the publication of the text.24 Another gloss (“I will refer you to the representation at the commencement of this record”; Abraham 1:12) was inserted interlineally, suggesting that “the references to the facsimiles within the text of the Book of Abraham seem to have been nineteenth-century editorial insertions”25 (although this is not the only interpretation of this data point).26

It should not come as a surprise that Joseph Smith (or his scribes) made revisions to the English text of the Book of Abraham and still called it a translation, since he also revised his revelations that comprise the Doctrine and Covenants and the Book of Mormon in subsequent editions after their initial publication.27

Whatever his precise method of translation, which Joseph specified no more than being “by the gift and power of God,” more important is what the Prophet produced. As Hugh Nibley recognized, “[T]he Prophet has saved us the trouble of faulting his method by announcing in no uncertain terms that it is a method unique to himself depending entirely on divine revelation. That places the whole thing beyond the reach of direct examination and criticism but leaves wide open the really effective means of testing any method, which is by the results it produces.”28 The results of Joseph Smith’s inspired translations are books of scripture that would have been beyond the Prophet’s natural ability to produce on his own. This is true for the Book of Abraham, which evinces numerous signs of having been derived from the ancient world as it claims and not from Joseph Smith’s fertile imagination or nineteenth-century environment.29

A fuller grasp of this fascinating and important subject therefore includes appreciating how Joseph Smith and other early Latter-day Saints used words such as “translation” in ways that are similar but also in some ways very different than how they are typically used today.30

Further Reading

Kerry Muhlestein, “Book of Abraham, translation of,” in The Pearl of Great Price Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2017), 63–69.

John Gee, “Joseph Smith and the Papyri,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 13–42.

Hugh Nibley, “Translated Correctly?” in The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2005), 51–65.

Robert J. Matthews, “Joseph Smith—Translator,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 77–87.

Footnotes

1 History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], 596; John Whitmer, History, 1831–circa 1847, 76; Warren Parrish, letter to the editor, Painesville Republican, 15 February 1838, cited in John Gee, “Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri,” FARMS Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 115n4.

2 Journal, 1835–1836, 47.

3 Editorial, circa 1 March 1842, Draft, 1.

4 “Book of Abraham,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 704, emphasis in original.

5 See the overview and discussion in Kerry Muhlestein, “Book of Abraham, translation of,” in The Pearl of Great Price Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2017), 63–69; cf. “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 32–39; Hugh Nibley, “Translated Correctly?” in The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 2005), 51–65; Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxii–xxvi.

6 “Church History,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 707.

7 David E. Sloan, “The Anthon Transcripts and the Translation of the Book of Mormon: Studying It Out in the Mind of Joseph Smith,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 57–81.

8 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017), 20.

9 For an overview, see Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 83–116; Brant A. Gardner, “Translating the Book of Mormon,” in A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine and History, ed. Laura Harris Hales (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2016), 21–32.

10 “Account of John, April 1829–C [D&C 7],” in The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, ed. Michael Hubbard MacKay et al. (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 47–48. For the historical context of this section, see Jeffrey G. Cannon, “Oliver Cowdery’s Gift,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 15–19.

11 “Chapter VI.,” in A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ, Organized according to Law, on the 6th of April, 1830 (Independence, MO: W. W. Phelps & Co., 1833), 18. In the Manuscript Revelation Book this section is called a “revelation” and not explicitly a “translation.” Revelation Book 1, 13.

12 History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], 15.

13 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 21; cf. MacKay et al., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 1, 48n129.

14 Letter to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 25 June 1833, [1]; Letter to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 2 July 1833, 52.

15 See generally Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 51–76; “The King James Bible and the Joseph Smith Translation,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 197–214; Royal Skousen, “The Earliest Textual Sources for Joseph Smith’s ‘New Translation ‘ of the King James Bible,” FARMS Review 17, no. 2 (2005): 451–470; The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon. Part Five: The King James Quotations in the Book of Mormon (Provo, Utah: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2019), 132–140.

16 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 21.

17 In fact, it appears that part of the process in revising some portions of the text of the “new translation” involved Joseph consulting popular biblical commentaries of his day. See “Joseph Smith’s Use of Bible Commentaries in His Translations,” LDS Perspectives Podcast, Episode 55.

18 Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxiii.

19 John Whitmer, History, 1831–circa 1847, 76.

20 Warren Parrish, letter to the editor, Painesville Republican, February 15, 1838.

21 Wilford Woodruff Journal, February 19, 1842, in Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1983), 2:155; Parley P. Pratt, “Editorials,” The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 3 (July 1, 1842): 47; Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer, October 3, 1846, 211; Orson Pratt, Journal of Discourses (August 25, 1878), 20:65. The account in the Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer reads thus: “[W]hen Joseph was reading the papyrus, he closed his eyes, and held a hat over his face, and that the revelation came to him; and that where the papyrus was torn, he could read the parts that were destroyed equally as well as those that were there; and that scribes sat by him writing, as he expounded.” The detail of Joseph placing his face into his hat to read the papyrus sounds much like how witnesses described the translation of the Book of Mormon, suggesting the possibility that the paper misreported or confused which text Lucy Mack Smith was describing.

22 See Pearl of Great Price Central, “Zeptah and Egyptes,” Book of Abraham Insight #8 (August 28, 2019).

23 Matthew J. Grey, “‘The Word of the Lord in the Original’’: Joseph Smith’s Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity, 249–302; Kerry Muhlestein and Megan Hansen, “‘The Work of Translating’: The Book of Abraham’s Translation Chronology,” in Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millett, ed. J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2016), 149–153.

24 Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 309n85.

25 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 143; Jensen and Hauglid, The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 195n57.

26 Kerry Muhlestein, “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 29–32; “The Explanation-Defying Book of Abraham,” in A Reason for Faith, 82; “Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: A Faithful, Egyptological Point of View,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 225–226.

27 See Royal Skousen, “Changes in The Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 11 (2014): 161–176; Marlin K. Jensen, “The Joseph Smith Papers: The Manuscript Revelation Books,” Ensign, July 2009, 47–51; Robin Scott Jensen, Richard E. Turley, Jr., and Riley M. Lorimer, eds., “Joseph Smith–Era Publications of Revelations,” in The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 2: Published Revelations (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2011), ix–xxxvi.

28 Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, 63.

29 As discussed in the Book of Abraham Insight articles posted here at Pearl of Great Price Central, as well as in Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 49–55, 97–105.

30 See further Robert J. Matthews, “Joseph Smith—Translator,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 77–87; Richard Lyman Bushman, “Joseph Smith as Translator,” in Believing History: Latter-day Saint Essays, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Jed Woodworth (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2004), 233–247; Alexander L. Baugh, “Joseph Smith: Seer, Translator, Revelator, and Prophet,” BYU devotional speech, June 24, 2014; “Joseph Smith as Revelator and Translator,” The Joseph Smith Papers Project.