Joseph Smith—History Insight #1

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are inspired by Joseph Smith’s account of his First Vision of God the Father and Jesus Christ as recorded in Joseph Smith–History in the Pearl of Great Price. Canonized as scripture on Sunday, October 10, 1880,1 this account of the First Vision has been enshrined for Latter-day Saints as the canonical narrative of the early life and prophetic calling of Joseph Smith.2

But while Latter-day Saints are mainly familiar with the canonical account of the First Vision that was first drafted by Joseph Smith in 1838–39, over the years historians have identified three other firsthand accounts of the First Vision left by the Prophet. As with the four canonical gospels in the New Testament that narrate the life and teachings of Jesus, the four primary accounts of the First Vision can be read individually to appreciate the nuance and subtle differences that they communicate in each retelling or they can be read together in harmony to appreciate them as an organic whole. Whether read individually or in harmony, each account communicates profound truths about God and Joseph Smith’s prophetic call.3

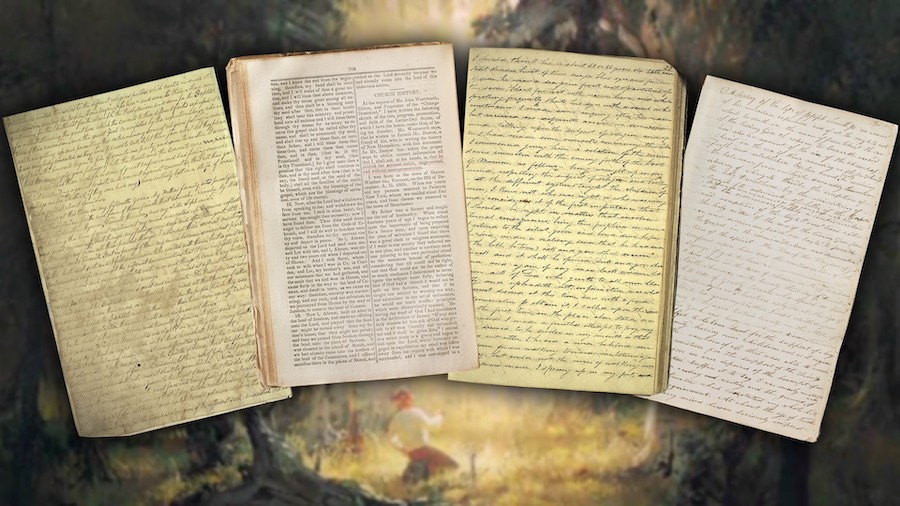

The primary accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision have been conveniently collected and digitized by the Joseph Smith Papers Project.4 They entail:

The 1832 Account: JS History, ca. Summer 1832, pp. 1–3.

This is the earliest account of the First Vision and is recorded in Joseph Smith’s own hand. It is a deeply personal and poignant narrative that is couched in Joseph’s quest to find forgiveness for his sins as a young man. It features an extended direct quotation of what the Lord instructed Joseph in the vision.

The 1835 Account: JS, Journal, 9–11 Nov. 1835, pp. 23–24.

This recitation of the First Vision stems from Joseph Smith’s encounter with the eccentric Robert Matthews in November 1835. Joseph and Matthews discussed religious matters during their meeting as both claimed prophetic authority. Part of the conversation included Joseph’s description of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon and the First Vision. This account includes the detail not present in other accounts that Joseph saw “many angels” in his vision of the Father and the Son.

The 1838 Account: JS History, 1838–1856, vol. A–1, pp. 2–3

Undoubtedly the most famous account of the First Vision, this recitation opened what later evolved into the six-volume History of the Church and was canonized in the Pearl of Great Price. Written at a time when the persecution of the Saints in Missouri was fresh on the Prophet’s mind, the tone of this retelling is more defensive and apologetic and emphasizes the theme of opposition against Joseph personally as well as his efforts to restore the Church of Jesus Christ.

Published in 1842 in the Church’s newspaper Times and Seasons, this account was prepared at the request of Chicago newspaperman John Wentworth. It was contextualized as part of a larger “sketch of the rise, progress, persecution, and faith of the Latter-Day Saints.” Peppered with Latin phrases, carefully crafted for wide public consumption, and drawing language from previously published records, this account of the First Vision shows the Prophet’s evolving literary style and reliance on clerks who helped him (re)formulate his narrative in later years.

The 1835, 1838, and 1842 accounts of the First Vision were copied or otherwise repurposed on a few occasions in Joseph Smith’s lifetime, attesting to their importance. As one historian has remarked, “Joseph Smith’s [F]irst [V]ision may be the best documented theophany in history. . . . Joseph Smith worked hard to document his experience in the grove, and scholars have worked hard to raise awareness of his several accounts.”5

Rather than feel threatened or bothered by the existence of multiple accounts of the First Vision, Latter-day Saints can rightly rejoice that they have access to additional records that compliment the canonical account in the Pearl of Great Price. As is true with all books of scripture, “The [F]irst [V]ision accounts were created in specific historical settings that shape what they say and how they say it. Each of the accounts of Joseph Smith’s [F]irst [V]ision has its own history. Each was created in circumstances that determined how it was remembered and communicated and thus how it was transmitted to us. Each account has gaps and omissions. Each adds detail and richness.”6

Further Reading

Steven C. Harper, “The First Vision: A Narrative from Joseph Smith’s Accounts” online at www.history.churchofjesuschrist.org.

Milton V. Backman Jr., “Joseph Smith’s Recitals of the First Vision,” Ensign, January 1985, 8–17.

James B. Allen and John W. Welch. “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820–1844, edited by John W. Welch, 2nd ed (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2017), 37–77.

Footnotes

1 “Fiftieth Semi-Annual Conference,” Deseret News (13 October 1880).

2 See the discussion and overview of the importance of the First Vision in Latter-day Saint thought in Terryl Givens, The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2019), 223-240; Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2019).

3 Richard J. Maynes, “The First Vision: Key to Truth,” Ensign, June 2017, 60–65.

4 See “Primary Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision of Deity,” online at the Joseph Smith Papers website.

5 Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: A Guide to the Historical Accounts (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 31.

6 Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 32.