Joseph Smith—History Insight #2

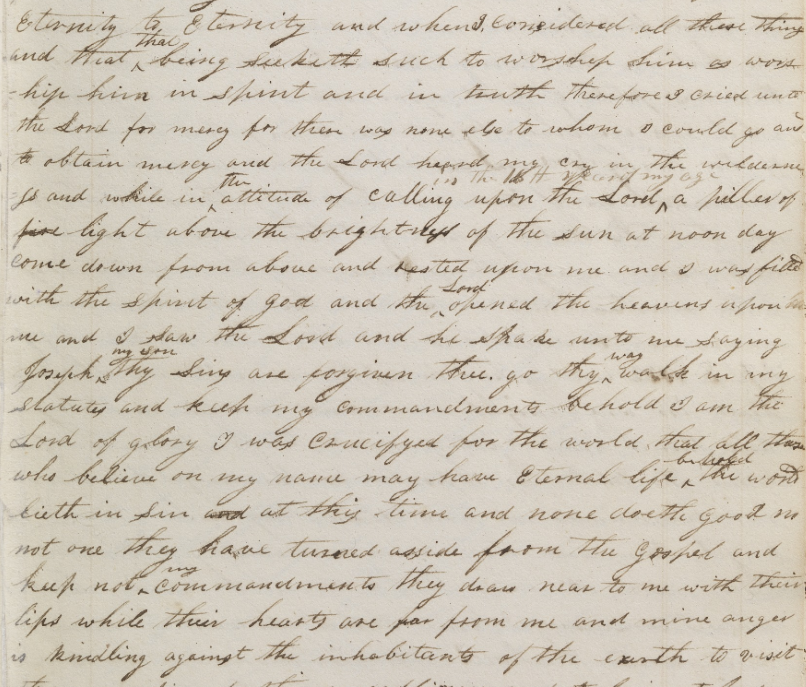

The earliest firsthand account of Joseph Smith’s First Vision was written in the summer of 1832.1 Part of a larger, ambitious historical narrative “of the life of Joseph Smith Jr.” that includes “an account of his marvilous experience” and “an account of the rise of the church of Christ in the eve of time,”2 this account of the First Vision is the only extant rendition that is preserved in the Prophet’s own hand.

The origin of the 1832 history that preserves this early account of the First Vision can be placed in the context of a shifting emphasis in recordkeeping among early Latter-day Saints. Spurred on by revelation commanding that a record and history be kept of the rise of the newly-formed Church of Christ (Doctrine and Covenants 21:1; 85:1–2), “the circa summer 1832 history came about as part of a new phase in [Joseph Smith]’s record-keeping practices. During the first four years of Mormon record keeping (1828–1831), [Joseph] focused primarily on preserving his revelatory texts. . . . This focus changed in 1832, when [Joseph] began documenting his personal life in detail for the first time, both in his history and in the journal he began on 27 November 1832.”3

“In the early 1830s,” note the editors of the Joseph Smith Papers Project, “when this history was written, it appears that [Joseph] had not broadcast the details of his first vision of Deity” with the possible exception of a hinting reference to the First Vision in an 1830 revelation.4

Initially, [Joseph] may have considered this vision to be a personal experience tied to his own religious explorations. He was not accustomed to recording personal events, and he did not initially record the vision as he later did the sacred texts at the center of his attention. Only when [Joseph] expanded his focus to include historical records did he write down a detailed account of the theophany he experienced as a youth. The result was a simple, unpolished account of his first “marvilous experience,” written largely in his own handwriting. The account was not published or widely circulated at the time, though in later years he told the story more frequently.5

It isn’t clear exactly when in 1832 this history was recorded, but a very likely time frame for its composition is sometime between July and November of that year.6 Frederick G. Williams assisted Joseph as a scribe to record the opening pages of this history. The way Joseph told this account of his vision was likely influenced, in part, by experiences he had while staying in Greenville, Indiana.7 That spring he traveled with Sidney Rigdon, Jesse Gause, Peter Whitmer Jr., and Newel K. Whitney to Missouri. On the way back to Ohio in May, Whitney broke his leg in a stagecoach accident, forcing Joseph to stay with him in Greenville to help him recover. During this time Joseph had plentiful opportunities to ponder on his standing before the Lord and reflect on the trials that faced him. Several of the prominent themes in the 1832 retelling of the First Vision parallel themes that appear in Joseph’s letters from his time in Greenville, which speak to the strong likelihood that at least the narrative and thematic seeds of the 1832 history were planted in Joseph’s mind during this time.8

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the 1832 account is that it does not explicitly speak of two personages visiting Joseph as later accounts do. Rather, it speaks of “the open[ing] the heavens upon [Joseph]” and Joseph then seeing “the Lord.”9 The reason for this apparent discrepancy with his later accounts has been explored by Latter-day Saint writers who argue that, while admittedly not as clear as the later accounts, the language of this account does not necessarily preclude the possibility of two personages being described.10

Another remarkable detail in this account of the vision is Joseph’s description of “a piller of fire light above the brightness of the sun at noon day” shining above him. Joseph appears to have struggled somewhat to communicate what he experienced in the vision, as he first wrote “fire” to describe what he saw but immediately crossed it out and replaced it with the word “light.”11 This gives a glimpse into Joseph’s struggle to describe his revelations with what he called “the little narrow prison . . . of paper[,] pen[,] and ink and a crooked[,] broken[,] scattered[,] and imperfect language.”12

After the Prophet’s death in 1844, the 1832 history traveled west with the Saints to Utah and was kept in the Church Historian’s Office. Being eclipsed in notoriety and importance by Joseph’s canonical 1838–39 account in the Pearl of Great Price, it went unpublished until 1965 when Paul Cheesman included a transcript of it in his master’s thesis.13 Since then, the 1832 account has been published and discussed multiple times (including in official Church publications) and has regained a prominent place in the historical consciousness of Latter-day Saints.14

Although the 1832 account of the First Vision may be “the least polished” of the extant renditions, it is without question the most intimate. The later retellings “are more conscious of the vision’s significance for all mankind, but none surpasses this earliest known account at revealing what it meant personally to young Joseph Smith.”15

Circa Summer 1832 History(Following the standardized version here; original available here) |

At about the age of twelve years, my mind become seriously impressed with regard to the all-important concerns for the welfare of my immortal soul, which led me to searching the scriptures—believing, as I was taught, that they contained the word of God and thus applying myself to them. My intimate acquaintance with those of different denominations led me to marvel exceedingly, for I discovered that they did not adorn their profession by a holy walk and godly conversation agreeable to what I found contained in that sacred depository. This was a grief to my soul. Thus, from the age of twelve years to fifteen I pondered many things in my heart concerning the situation of the world of mankind, the contentions and divisions, the wickedness and abominations, and the darkness which pervaded the minds of mankind. My mind became exceedingly distressed, for I became convicted of my sins, and by searching the scriptures I found that mankind did not come unto the Lord but that they had apostatized from the true and living faith, and there was no society or denomination that was built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament. I felt to mourn for my own sins and for the sins of the world, for I learned in the scriptures that God was the same yesterday, today, and forever, that he was no respecter of persons, for he was God. For I looked upon the sun, the glorious luminary of the earth, and also the moon, rolling in their majesty through the heavens, and also the stars shining in their courses, and the earth also upon which I stood, and the beasts of the field, and the fowls of heaven, and the fish of the waters, and also man walking forth upon the face of the earth in majesty and in the strength of beauty, whose power and intelligence in governing the things which are so exceedingly great and marvelous, even in the likeness of him who created them. And when I considered upon these things, my heart exclaimed, “Well hath the wise man said, ‘It is a fool that saith in his heart, there is no God.’” My heart exclaimed, “All, all these bear testimony and bespeak an omnipotent and omnipresent power, a being who maketh laws and decreeth and bindeth all things in their bounds, who filleth eternity, who was and is and will be from all eternity to eternity.” And I considered all these things and that that being seeketh such to worship him as worship him in spirit and in truth. Therefore, I cried unto the Lord for mercy, for there was none else to whom I could go and obtain mercy. And the Lord heard my cry in the wilderness, and while in the attitude of calling upon the Lord, in the sixteenth year of my age, a pillar of light above the brightness of the sun at noonday came down from above and rested upon me. I was filled with the spirit of God, and the Lord opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord. And he spake unto me, saying, “Joseph, my son, thy sins are forgiven thee. Go thy way, walk in my statutes, and keep my commandments. Behold, I am the Lord of glory. I was crucified for the world, that all those who believe on my name may have eternal life. Behold, the world lieth in sin at this time, and none doeth good, no, not one. They have turned aside from the gospel and keep not my commandments. They draw near to me with their lips while their hearts are far from me. And mine anger is kindling against the inhabitants of the earth, to visit them according to their ungodliness and to bring to pass that which hath been spoken by the mouth of the prophets and apostles. Behold and lo, I come quickly, as it is written of me, in the cloud, clothed in the glory of my Father.” My soul was filled with love, and for many days I could rejoice with great joy. The Lord was with me, but I could find none that would believe the heavenly vision. Nevertheless, I pondered these things in my heart. |

Further Reading

Karen Lynn Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844 (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 3–23.

James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2017), 37–77.

Dean C. Jessee, “The Early Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (1969): 275–294.

Footnotes

1 See History, circa Summer 1832; cf. Karen Lynn Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844 (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 3–23.

2 History, circa Summer 1832, 1.

3 Davidson et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 6.

4 See Articles and Covenants, ca. Apr. 1830 [D&C 20:5]; cf. Michael Hubbard MacKay et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831 (Salt Lake City, UT: Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 121.

5 Davidson et al., eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 6.

6 Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: A Guide to the Historical Accounts (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 34.

7 Matthew C. Godfrey, “The Second Sacred Grove: The Influence of Greenville, Indiana, on Joseph Smith’s 1832 First Vision Account,” Journal of Mormon History 44, no. 4 (October 2018): 1–18.

8 See Godfrey, “The Second Sacred Grove,” 15–18.

9 History, circa Summer 1832, 3.

10 James B. Allen, “Eight Contemporary Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision—What Do We Learn from Them?” Improvement Era, April 1970, 7; Matthew B. Brown, A Pillar of Light: The History and Message of the First Vision (American Fork, UT: Covenant, 2009), 92–94; Steven C. Harper, “A Seeker’s Guide to the Historical Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 12, no. 1 (2011): 168; James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestation, 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd ed (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2017), 66–67.

11 History, circa Summer 1832, 3.

12 Letter to William W. Phelps, 27 November 1832, in Letterbook 1, p. 4; cf. Matthew C. Godfrey et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833 (Salt Lake City, UT: Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 320.

13 Paul R. Cheesman, An Analysis of the Accounts Relating Joseph Smith’s Early Visions (Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, 1965), 126–132.

14 Dean C. Jessee, “The Early Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” BYU Studies 9, no. 3 (1969): 278–280; Allen, “Eight Contemporary Accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision—What Do We Learn from Them?” 4–13; Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971; 2nd edition, 1980), 155–157; “Joseph Smith’s Recitals of the First Vision,” Ensign, January 1985, 8–17; Eyewitness Accounts of the Restoration (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986), 17–32; Dean C. Jessee, ed. The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1984. rep. ed. 2002), 4–6; The Papers of Joseph Smith, Volume 1: Autobiographical and Historical Writings (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989), 3–10; Anderson, “Joseph Smith’s Testimony of the First Vision,” 10–21; Ronald O. Barney, “The First Vision: Searching for the Truth,” Ensign, January 2005, 14–19; Brown, A Pillar of Light, 178–180; Davidson et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1, 10–16; MacKay et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 1, 279–285; Allen and Welch. “Analysis of Joseph Smith’s Accounts of His First Vision,” 37–77; Richard J. Maynes, “The First Vision: Key to Truth,” Ensign, June 2017, 60–65.

15 Harper, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, 33.