Book of Abraham Insight #14

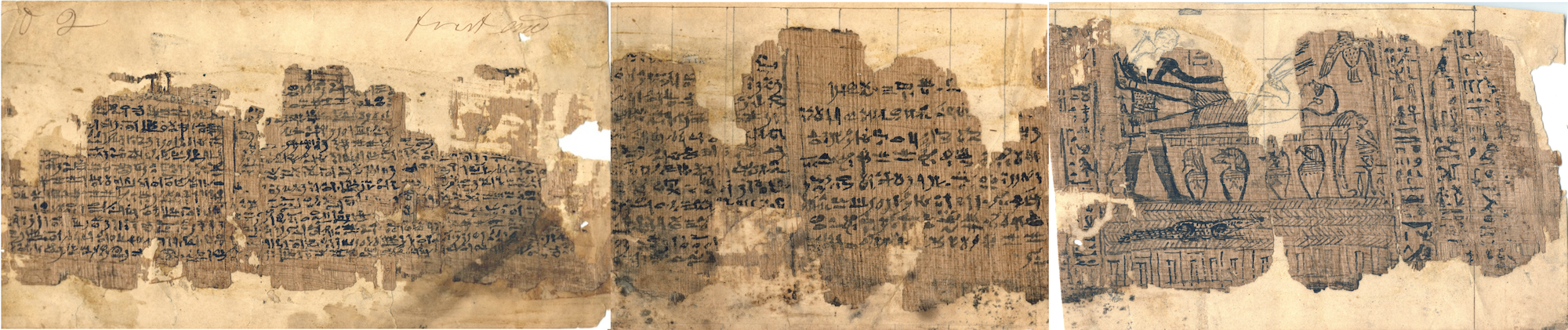

Thanks to the work of Egyptologists over the past decades, in addition to knowing what texts the extant Egyptian papyri acquired by Joseph Smith in 1835 contain,1 we also know quite a bit about the ancient owners of the papyri. “From the names, titles, and genealogies written on the Joseph Smith Papyri, we know” the owner of the papyri designated Joseph Smith Papyri I, XI, and X (from which Joseph Smith got Facsimiles 1 and 3) was a man named Hor (or Horos in Greek).2

Hor lived “about the same time period as the Rosetta Stone,” that is, around 200 BC, and was a priest or prophet of three Egyptian deities in the ancient city of Thebes.3 “As prophet, he was a spokesman for various gods, who interacted with prophets on a regular basis. As a prophet, Hor had been initiated into the temple’s sacred places, which represented heaven, and had promised to maintain strict standards of personal conduct and purity.”4

Being a priest or prophet in ancient Egypt had its privileges. For example, a prophet like Hor “had access to the great Theban temple libraries, containing narratives, reference works, and manuals, as well as scrolls on religion, ritual, and history.”5 Hor lived at a time when Egyptian religion was eclectic, with elements of “Greek, Jewish, and Near Eastern traditions” making their way into Egyptian culture during this time.6 “The papyri owners also lived at a time when stories about Abraham circulated in Egypt. If any ancient Egyptians were in a position to know about Abraham, it was the Theban priests.”7

The first god for whom Hor served as a prophet was Amun-Re, whose magnificent temple still stands today in modern Luxor, Egypt. As a prophet of this god, Hor “would have gone into the holy of holies and would have encountered the statue of the deity face to face. He also would have participated in the daily execration ritual, in which a wax figure of an enemy was spat upon, trampled under the left foot, smitten with a spear, bound, and placed on the fire. He also would have known a creation account that starts with God creating light and then separating out the dry land from the water, followed by the creation of multiple gods who together plan the creation, cause the sun to appear, and vanquish evil.”8

Hor was also a prophet of a god named Min-Who-Massacres-His-Enemies. This lesser-known god was a syncretized or combined deity between the Egyptian god Min and the Canaanite warrior-god Resheph. “This deity was worshipped by performing human sacrifice in effigy. Two rituals are known for certain: one involves the subduing of sinners by binding them, and the other involves slaying enemies and burning them on an altar. These rituals seem to have also been part of the execration ritual that [Hor] would have performed as prophet of [Amun-Re].”9

Finally, Hor was a prophet for the god Khonsu (or Chespisichis in Greek). In this capacity he “was involved in a temple that dealt with healing people and protecting them from demons. The founding narrative of this temple deals with a pharaoh who had extensive contact with far-flung foreign lands, who takes any woman he thinks is beautiful as a wife, and who asks for and receives directions from God. The narrative also deals with the appearance of angels and God appearing in dreams to give instructions.”10

By knowing these details about Hor and his occupation we can say something about the plausibility of a text like the Book of Abraham having attracted his interest or having come into his possession, or at the very least why the illustrations from his papyri (Facsimiles 1 and 3) were used by Joseph Smith to illustrate the Book of Abraham.

As a priest in Thebes, Hor would have been highly literate and would have had access to texts about Abraham and other Jewish figures.11 As a prophet of Amun-Re he would have had an interest in themes such as temple initiation, seeing God face-to-face, and creation. As a prophet of both Amun-Re and Min-Who-Massacres-His-Enemies he would have “had a professional interest in . . . stories about slaughtering and then burning people on an altar.”12 Finally, as a prophet of the god Khonsu or Chespisichis he would have been attracted to a text that featured angels, contact with foreign lands, and a king who takes any woman he thinks is beautiful. These elements are, of course, prominent in the Book of Abraham.

While this does not prove that Hor had a copy of the Book of Abraham, it does reinforce the plausibility that he could have taken an interest in a text like the Book of Abraham and would have wanted to retain a copy for himself which then fell into the hands of Joseph Smith many centuries later.

Further Reading

John Gee, “The Ancient Owners of the Papyri,” in An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2017), 57–72.

Kerry Muhlestein, “The Religious and Cultural Background of Joseph Smith Papyrus I,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 20–33.

John Gee, “Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri,” FARMS Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 113–137, esp. 123–135.

John Gee, “The Ancient Owners of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” FARMS Report (1999).

Footnotes

1 Hugh W. Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005); Michael Rhodes, The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002); Books of the Dead Belonging to Tshemmin and Neferirnub: A Translation and Commentary (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2010).

2 John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2017), 58; cf. Marc Coenen, “The Dating of the Papyri Joseph Smith I, X, and XI and Min Who Massacres His Enemies,” in Egyptian Religion: The Last Thousand Years, Part II: Studies Dedicated to the Memory or Jan Quaegebeur, ed. Willy Clarysse, Antoon Schoors, and Harco Willems (Leuven: Peeters, 1998), 1103–1115; “Horos, Prophet of Min Who Massacres His Enemies,” Chronique D’Égypte LXXIV (1999): 257–260; John Gee, “History of a Theban Priesthood,” in «Et Maintenant Ce Ne Sont Plus Que Des Villages…» Thèbes et Sa Région aux Époques Hellénistique, Romaine et Byzantine, Actes du Colloque Tenu À Bruxelles les 2 et 3 Décembre 2005, ed. Alain Delattre and Paul Heilporn (Bruxelles: Assocation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 2008), 59–71; “Horos Son of Osoroeris,” in Mélanges offerts à Ola el-Aguizy, ed. Fayza Haikal (Paris: Institute Français D’Archéologie Orientale, 2015), 169–178.

3 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 59.

4 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 59.

5 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 59–61.

6 Jacco Dieleman, “Coping with a Difficult Life: Magic, Healing, and Sacred Knowledge,” in The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt, ed. Christina Riggs (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), 339.

7 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 61.

8 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 61.

9 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 61; cf. John Gee, “Execration Rituals in Various Temples,” in 8. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Interconnections between Temples, Warschau, 22.–25. September 2008, ed. Monika Dolińska and Horst Beinlich (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010), 67–80; Coenen, “The Dating of the Papyri Joseph Smith I, X, and XI and Min Who Massacres His Enemies,” 1112–1113.

10 Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 61–63; cf. John Gee, “The Cult of Chespisichis,” in Egypt in Transition: Social and Religious Development of Egypt in the First Millennium BCE, ed. Ladislav Bareš, Filip Coppens, and Kvĕta Smoláriková (Prauge: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University in Prague, 2010), 129–145.

11 Kerry Muhlestein, “Abraham, Isaac, and Osiris–Michael: The Use of Biblical Figures in Egyptian Religion, A Survey,” in Achievements and Problems of Modern Egyptology: Proceedings of the International Conference Held in Moscow on September 29–October 2, 2009, ed. Galina A. Belova (Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, Center for Egyptological Studies, 2011), 246–259; Kerry Muhlestein, “The Religious and Cultural Background of Joseph Smith Papyrus I,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 20–33.

12 John Gee, “Some Puzzles from the Joseph Smith Papyri,” FARMS Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 128.